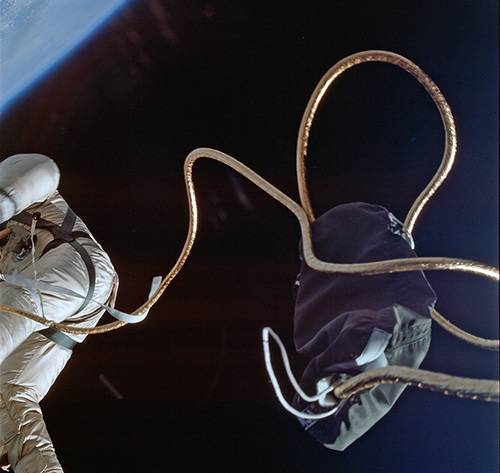

Ed White floats beside Gemini IV, with the Gulf of California behind him, in the first American spacewalk.

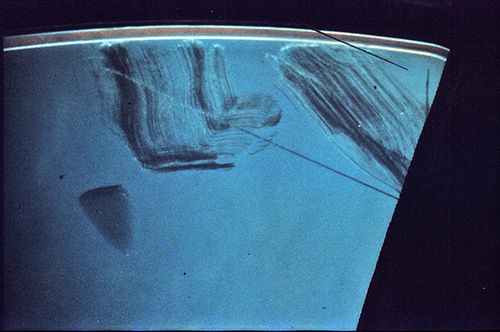

A frame from a 16mm movie camera which recorded his EVA.

Gemini IV

4 – 8 June 1965 AEST

America’s first EVA.

Ed White floats beside Gemini IV, with the Gulf of California behind him, in the first American spacewalk. A frame from a 16mm movie camera which recorded his EVA. |

Command Pilot – James McDivitt.

Pilot – Edward White II.

Back up crew:

Command Pilot – Frank Borman.

Pilot – James Lovell Jr.

Fact box: |

|

| Gemini Spacecraft No. 4 | |

| Launch | 1515:59 UT 1015:59 USEST Thursday 3 June 1965 (0115:59 AEST 4 June 1965) |

| Splashdown | 1712:11 UT Monday 7 June 1965 (0312:11 AEST 8 June 1965) |

| Splashdown location | 27° 44'N by 74° 11'W |

| Mission duration | 97 hours 56 minutes 12 seconds 4 days 1 hour 56 minutes 12 seconds. |

| Inclination | 32.5° |

| Orbits | 66 orbits 62 revs |

| Apogee | Between 257 and 283 kilometres |

| Perigee | Between 158 and 161 kilometres |

| Period | 88.94 minutes |

| Total distance travelled | 2,590,561 kilometres. |

| Spacecraft mass | 3,570 kilograms |

| EVA | 21 minutes by pilot |

Originally the first Gemini EVA (Extra Vehicular Activity, commonly called a spacewalk), was scheduled for Gemini VI.

Due to the Russian Aleksei Leonov’s walk on 18 March 1965, and the American spacewalk suits and systems being announced as ready for use ahead of schedule, NASA began looking at bringing the spacewalk forward.

Although Grissom and Young were unsuccessful in depressurising the cabin and opening the hatch during one of their Gemini III simulations, the NASA hierarchy did reluctantly agree to have White stand up on his seat. However, after Leonov’s walk, President Johnson is supposed to have snarled, “If the guy can stick his head out, he can also take a walk. I want to see an American EVA.”

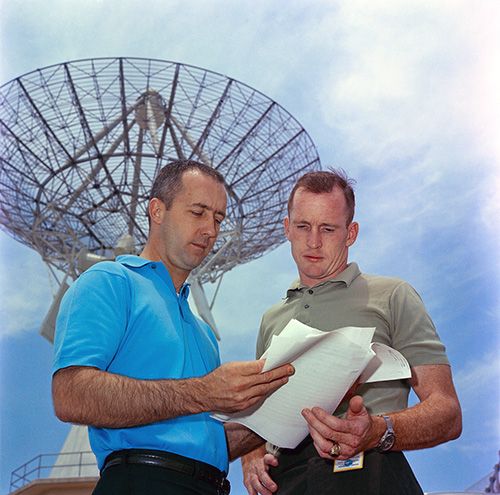

Jim McDivitt and Ed White at Cape Canaveral before the mission. |

The EVA plan was kept secret.

Although there had been references to an EVA in Gemini IV, first stated in January 1964 and it was publicly mentioned by Gemini Deputy Manager Kenneth Kleinknecht at a press briefing in July 1964, NASA management were not committing themselves: “… we shouldn’t be putting guys in a vacuum with nothing between them but the little old lady from Worcester and her glue pot," they warned, referring to the seamstresses at the suit manufacturing plant of the David Clark Company, in Worcester, Massachusetts.

So a Gemini IV EVA was kept a secret with only people directly involved in the know. Flight Director Gene Kranz went into overdrive and worked his normal day preparing for the mission, but in the evening he returned to work in secret on the EVA procedures. Kranz planned to have the hardware qualified and procedures for the EVA ready fourteen days before the launch.

The remote tracking station Capcoms were given double-sealed envelopes and told to only open them on instructions from Flight Director Gene Kranz. If no instruction was issued, the envelopes were to be returned unopened. Inside was another envelope marked Plan X detailing procedures for an EVA. It wasn’t until the final week of training, on 25 May 1965, that the message from HQ arrived “We are GO for EVA,” and the media were informed.

Carnarvon Capcom Ed Fendell, writing in 2012:

“I carried with me to the site, unknown to anyone, including my own team, a secret flight plan called Flight Plan X that I and several others had worked on in secret back in Houston. It was the Flight plan for our first EVA, which we then used on that mission. Over CRO I gave the crew the go to commence with the EVA and for Ed White to exit the spacecraft. Very exciting.”

The crew.

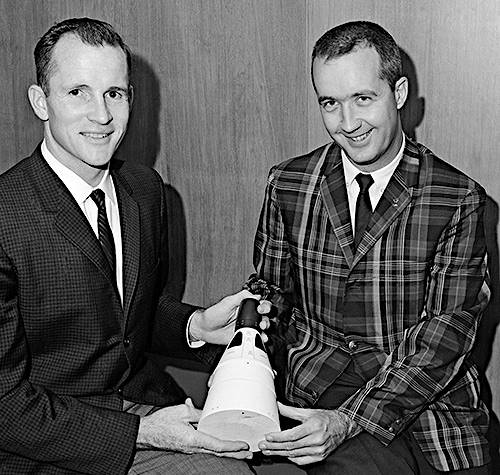

The crew for Gemini IV was announced on 27 July 1964. Command Pilot James McDivitt and Pilot Edward White had known each other since their college days and had been in the same class at the Air Force Test School. Backup crew Frank Borman and James Lovell, both 36, first met when undergoing testing by NASA. All four were second generation astronauts, selected by NASA in September 1962.

Ed White and James McDivitt in a 1962 NASA photo. |

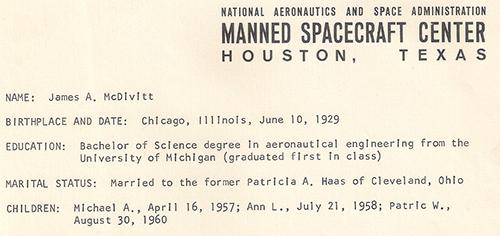

James Alton McDivitt, aged 35 for the mission, was born in Chicago, Illinois, on 10 June 1929 and went to school in Kalamazoo, Michigan. He received his BSc. in aeronautical engineering from the University of Michigan (first in class) in 1959, and an Honarary Doctorate in Astronautical Science from the same University in 1965. He joined the Air Force in 1951, fighting in the Korean War, and retired with the rank of Brigadier-General when he retired from NASA in June 1972. He logged more than 5,000 flying hours. He joined NASA in the second intake in September 1962, and this was his first space flight. He commanded the Apollo 9 Earth orbiting mission, and was Program Manager for Apollos 12 through 16. He regards his highlight in space was getting Apollo 13 home safely.

James McDivitt biographical notes, released before the mission. |

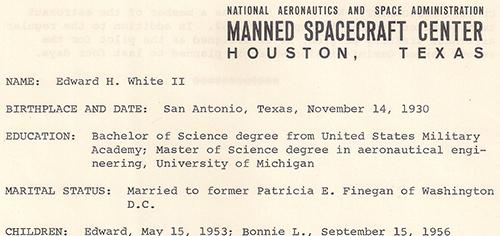

Edward Higgins White II, aged 34, was born in San Antonio, Texas, on 14 November 1930. In 1952 he earned his BSc. at the US Military Academy at West Point. He attended the Air Force Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, California in 1959 and later was assigned to the Wright-Patterson Air Force as an experimental test pilot. White logged more than 3,000 hours flying, 2,200 in jets. He joined NASA in September 1962 in the second intake of astronauts.

White was ideal for the first American attempt to walk in space; a fitness fanatic and superb athlete, he just missed out on the US team for the 400 metre Olympic hurdles by 0.4 of a second. He died in the tragic Apollo 1 fire on 27 January 1967.

Edward White biographical notes, released before the mission. |

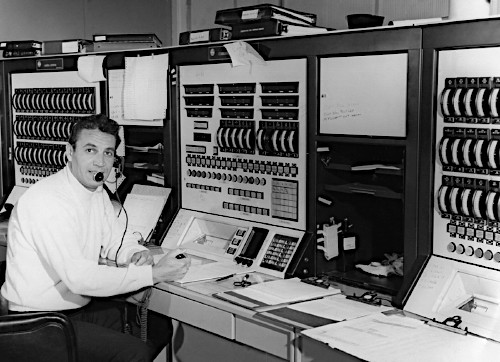

The new Mission Control Center in Houston (MCC-H) opens for business.

This mission was the first time the new Mission Control Center in Houston, Texas, was used. New technology was to be tried and it was the first time Houston had three 8 hour shifts covering 24 hours a day. Chris Kraft, as well as Mission Director, was Flight Director of the Red Team covering the working day operations; Gene Kranz and his White Team was the Systems Shift, checking the status of the ship and its consumables and put the astronauts to sleep; while John Hodge’s Blue Team was the real-time planning shift.

Gemini IV, with Houston as the Flight Control Center, served as a training ground for astronauts, flight controllers, technical staff and tracking stations, setting the style for the later Gemini missions, as well as for future Apollo flights.

At the tracking stations we were used to “This is the Cape…” coming down the line; now we heard this new identification, “This is Houston…”, in our earphones when Mission Control called us.

The brand new Mission Control Center in Houston during GT-4. |

The Flight Control Team at Carnarvon.

This was the first time an astronaut was not the Capcom at Carnarvon, but an observer. Dave Scott (Gemini VIII, Apollos 9 and 15) was our astronaut/observer for Gemini IV. After the Capcom fracas of Gemini III we settled down to follow our leader and Capcom, Ed Fendell.

The Gemini 4 Flight Control team at Carnarvon. 1. Dick Simons (M&O) 5. Dr Bill Walsh (RAAF Flight Surgeon) Photo: Hamish Lindsay. Identification: Ed Fendell and Hamish Lindsay. Updated scan from the 120 negative: Colin Mackellar. |

Here’s a version which has been colourised (with limited success!). |

Ed Fendell, writing in 2012: “Carnarvon was an unbelievable place in those days. … The Capcom job was the best job I ever had in my life, and the memories that went with it stay with me to this day.” |

Ed was a stickler for intercom protocol and discipline, and drilled us mercilessly until we reached his high standard of prompt, efficient reporting.

Ed had a streak of humour, which surfaced sometimes on the intercom. He and Monte Sala, our Digital Command System engineer, working closely together during the mission, would mock each other’s accents on the loop – Ed’s American and Monte’s Italian. Then one night (we always worked at night as it was the Americans’ day) Ed suggested Monte go outside and have a wash. The humour of that suggestive remark wasn’t explained until we walked outside and saw that Ed had poured a packet of detergent into Monte’s fountain and the suds foamed up all over the spacecraft model.

Station engineer Monte Sala with the fountain he designed for AWA. |

Ed later became famous as ‘Captain Video,’ remotely controlling the Lunar Rovers’ television cameras during the later Apollo missions.

It was Ed who received the Plan X secret instructions for an EVA just before launch.

New shifts for tracking stations to cope with long duration missions.

This mission was our first taste of long duration missions where our shifts cycled with the spacecraft’s cluster of station overhead passes. It would then drift away from us and fly over India and South America with minimal tracking facilities, when we could get some rest, though some critical personnel had to sleep on standby on site.

For example we could be busy tracking through a group of 7 station passes, say orbits 13 through 19, then we would go home to sleep for 9 orbits and return to the station to support passes 28 through 34, and so on through the mission. It was a 14-hour day at work followed by a 10 hour break, sliding forward 1 hour earlier each shift for the length of the mission.

The passes would begin in the north-east with a short glimpse of the spacecraft for around a minute, peak overhead with longer passes of up to 12 minutes and then fade out in the north-west with short passes again before it disappeared below the horizon to go through the whole cycle again.

John Ferry, a member of the Gemini flight control team, monitored communications and station operations from the Capcom console when the spacecraft was on orbits which were not visible from the station, allowing others to get some sleep. Photo: Hamish Lindsay. |

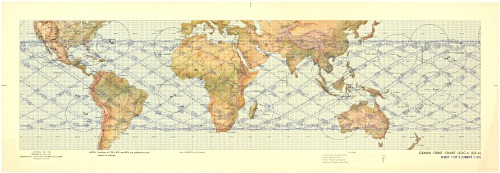

A Gemini IV groundtrack chart, for Orbits 1–22, kept and scanned by Hamish Lindsay. Large (460kb), Largest (1.0MB). |

Four days in space were planned – longer than all the NASA Mercury and Gemini flights combined at that point. Objectives of the mission were to trial the first American spacewalk, evaluate the prolonged effects of spaceflight over 4 days on the crew and the spacecraft, looking at crew rest and work cycles, eating schedules and real time flight planning. In addition they planned to try station keeping with the second stage of the Launch Vehicle, and in-and-out of plane manoeuvres. There were 11 experiments scheduled.

James McDivitt and Edward White walk from the transfer van to the launch vehicle. |

At T-35 minutes before launch, the erector stuck at 12° while being lowered. It was raised and lowered again, but still stuck. After an hour of investigation, technicians found a faulty connector in a junction box. It was replaced and after a delay of 1 hour 16 minutes the count continued to launch.

Launch.

At 1015:59 USEST on Thursday 3 June 1965 the 27 metre tall GLV Titan II rocket thrust the Gemini IV capsule into the sky from Launch Complex-19 into an initial elliptical orbit of 163 by 282 kilometres. It had the first international television audience, 12 European nations watching it through the Early Bird satellite.

Gemini 4 roars off the luanch pad on 3rd June 1965 (US time). |

McDivitt reported booster cut-off 5½ minutes after lift-off and waited before backing off, using his thrusters. Then, once in orbit, McDivitt and White tried to catch up with their discarded booster rocket. White saw the rocket venting, with propellant streaming from its nozzles. McDivitt estimated it was 120 metres away, while White thought it was more like 75 metres.

McDivitt called down 7¼ minutes after launch, “Okay, I got the old second stage. It’s spinning away and looks pretty.”

Grissom, “Roger. You say it’s spinning away?”

McDivitt, “Roger. It’s starting to tumble a little.”

Grissom, “Hey Jim. How fast is that booster tumbling?”

McDivitt, “I can’t give you that… going around.”

Grissom, “Is it just slowly rotating?”

McDivitt, “Roger. It’s slowly rotating.”

McDivitt aimed the spacecraft at the booster and thrust forward towards it. After two bursts from his thrusters the booster seemed to move away and downwards. McDivitt pitched the nose downwards and they saw the rocket again, apparently on a different track. He tried several times to reach the booster but with no luck. They couldn’t approach the target. By nightfall the booster appeared to be about 600 metres away, and with the dawn it was 3 to 5 kilometres away. As the flight engineers were still learning orbital mechanics and rendezvous techniques, McDivitt, who was only eyeballing his manoeuvres, gave up when their Orbital Attitude Manoeuvring System (OAMS) fuel quickly ran down to half. Gemini IV had a limited fuel supply – its tanks were only half the size of later spacecraft.

The reason McDivitt failed to reach the booster was an ignorance of orbital mechanics. On Earth to reach a target you can accelerate in a straight line towards it. In orbit adding speed raises altitude, moving you into a higher orbit, so you are travelling further away and slower than the target, which is what happened to Gemini IV. McDivitt should have slowed into a lower orbit, thus speeding up and passing the target, then at the appropriate moment speeding up to join the target’s plane. Once next to the target all relative motion between them is eliminated and the spacecraft can approach the target directly.

Carnarvon First Pass.

During the first pass over Carnarvon at 0:43:41 GET (0159:40 AEST) McDivitt explained, “The booster fell away quite rapidly and got below us like there was a considerable difference in our velocity, and I let the thing get too far from me.”

Over the tracking station at Kano, Africa, into the second orbit the spacecraft was travelling sideways as they entered the night; White called down, “A very interesting thing – Jim’s got full daylight out his window, and I have full night out of mine. It seems very strange for me to look out Jim’s side and see daylight and look out my side and it’s just pitch black.”

Down among the consoles in Mission Control John Aaron, the Red Team’s leader in charge of the Gemini life support, electrical and communications systems, looked at Chris Kraft and said “We’re go for EVA, Flight.”

Chris Kraft at his console during Gemini IV. |

Carnarvon Second Pass.

On the second pass over Carnarvon, at 2:24:22 GET (0340:21 AEST) the astronauts were finding conditions very difficult, and McDivitt called to the Carnarvon Capcom, Ed Fendell:

"Listen, you might advise Flight that we are running late on this thing. There’s a lot to do and we are having trouble keeping track of all this stuff. I’ll give you a blood pressure as soon as I get around to it."

Fendell: “Full scale on your blood pressure.”

McDivitt: “I don’t think you got a good blood pressure the bulb popped off.”

Fendell: “Gemini 4 you are GO for EVA and decompression. Disregard the blood pressure unless you have got some minutes and then try and get it for us. We’d appreciate it.”

McDivitt snapped back: “We don’t have any time at all. We’re really pressed here.”

Fendell: “We’re not going to say anything here on the ground. If you need anything we’ll wait.”McDivitt: “Okay. Listen, has Houston been advised yet we’re runnin’ a little late and we might not be ready at Hawaii?”

Fendell: "Okay. He’s ready he knows that. Houston advises you can use any attitude you like for your extra vehicular activity.”

With the cabin rather a jumble of items, and McDivitt feeling they would be too rushed this time around, he decided to delay the EVA until the next orbit, so we had to wait for another pass before the big event.

Jim McDivitt aboard Gemini IV in this underexposed photo. |

At 3:00:19 GET (1316:18 USEST) the Houston Capcom told the crew,

“Jim, you’re going to be live (on television) as you make your pass across the States this time.”

McDivitt, “Okay. Anything in particular you want me to say?”

Grissom, “Suit yourself.”

McDivitt, “Okay.”

Four minutes later, approaching the American coast, Grissom asked,

“How about describing the way the cockpit is laid out now, with all of your gear out?”

McDivitt, “Okay, well we’ve got to the get-out position here. Ed has most of the equipment on him right now. I’ve got the gun and the camera and the hatch fitting – the fitting to tie the two suit hoses together. Ed has all the paraphernalia on him right now, but he’s on the suit circuit. I think when we get over Africa we’re going to go through the checklist again and when we get to Carnarvon we’ll be all set.”

Grissom, “Roger. Have you taken any pictures yet?”

McDivitt, “No. As a matter of fact we really haven’t had the time to do much.”

Grissom, “You haven’t had any time yet, have you?”

McDivitt, “It’s a nice spacecraft though, Gus.”

The Nile Delta and Sinai as see from Gemini IV. |

Carnarvon Third Pass.

On the third pass over Carnarvon at 3:57:34 GET (0513:33 AEST) McDivitt checked:

“We have a GO to start the decompression, is that right?”

Fendell: “That’s affirm, a GO for decompression and a GO for EVA.”

McDivitt: “Roger. We expect to be out by the time we get near Hawaii.”

Recording starts at acquisition at 03:57:34 GET. 2.1MB mp3 file, 3 minutes 47 seconds. Tape recorded and preserved by Hamish Lindsay. Digitised and edited by Colin Mackellar. (More Carnarvon audio here.) |

At 4:07:42 GET (0523:41 AEST) McDivitt announced to White on the on-board recorder, “We’re going to vent the cabin now.”

White answered, “Yes.”

Just over three minutes later White said, “We’re in a vacuum now and the right suit is holding at 4 (psi = 27.6 kPa) and the flow is satisfactory. I’m not overly warm.”

McDivitt, “Roger. We’ve got the cabin vent valve open….. cabin (pressure) at zero. Time to unlock the hatch.”

The astronauts began preparations for the first American spacewalk after they were given the GO for EVA over Cape Canaveral by Capcom Gus Grissom. After depressurizing the cabin they had trouble opening the hatch – it would not unlatch because a spring failed to compress. After yanking and poking around the hatch ratchet it suddenly cracked open. Then White found it as hard to open wide in zero-g as it was on the ground back on Earth.

As White prepared to climb out he asked, “Am I clobbering the switches, Jim?”

McDivitt, “Yes, you’re really all over ’em, Ed.”

Recording starts at 04:23:01 GET, with Hawaii Capcom calling Gemini IV. 16MB mp3 file, 33 minutes 41 seconds. Tape recorded and preserved by Hamish Lindsay. |

Gemini IV was 193 kilometres above Hawaii at 4:23:19 GET (0539:18 AEST) when McDivitt said, “We’re going to put you on record so the whole world can hear this later on.”

White, “All right.”

The smooth Public Affairs voice announced, "This is Gemini Control. Four hours and twenty four minutes into the mission. The Hawaii station has just established contact and the pilot, Jim McDivitt advises the cabin has been depressurised. It is reading zero. We are standing by for a GO from Hawaii to open the hatch… White has opened the hatch… he has stood up. McDivitt reports that White is standing on the seat."

Author:

“At Carnarvon we were all getting ready for the next pass, but hanging onto every word coming down the voice channel from Houston. To us this first spacewalk was one of the supreme moments of the Gemini Program, and we were agog to hear how it was going, and what we would find when they came up over our horizon. There was so much to go wrong.”

White,

“I was waiting for the GO and it came a little earlier than I expected. I was expecting it over Guaymas. I thought maybe I had lost track of time up there – it was going faster than I had anticipated. Chris Kraft had thought we were ready to go over Hawaii, and since we were going to lose a portion of the night time on the other end of the EVA due to the late launch he decided to let us go over Hawaii.”

The Spacewalk EVA Begins.

While the spacecraft was travelling between Hawaii and Mexico, White eased himself out of the hatch with the manoeuvring unit, or gun. A glove he had left on the seat seemed to acquire a mind of its own – it rose off the seat and gently drifted out of the hatch after him to waft off into space.

White called, “I’m outside the spacecraft, as a matter of fact.”

McDivitt, “He has the hatch open. He’s standing in the seat.”

Hawaii Capcom, “Roger. Houston will give you a GO/NOGO to exit spacecraft over Guaymas.”

Capcom, “Roger. Everything looks good here. What do you think?”

Capcom, “We’re happy with it. Everything looks good on the ground, Gemini 4.”

McDivitt, “When he’s moving around out there he’s really rocking the spacecraft around.”

At 4:28:14 GET (0544:13 AEST Friday 4 June) the Hawaii Capcom told the spacecraft,

“We just had word from Houston. We’re ready to have you get out whenever you’re ready. Give us a mark when you egress the spacecraft.”

McDivitt, “Okay. We’ve got our GO now. Is that right?”

Capcom, “Affirmative. Be sure and give us a mark when he egresses.”

At 4:30:19 GET (0546:18 AEST) White announced, “Okay. I’m separating from the spacecraft.”

McDivitt, “He’s separating from the spacecraft at this time Hawaii.”

White, “Okay. My feet are out.”

White, “I think I’m dragging a little bit, but I don’t want to fire the gun yet.”

White soars into space.

At 4:30:36 GET (0546:35 AEST) came the moment White drifted clear of the spacecraft with, “Okay. I’m out.”

McDivitt, “OK, he’s out. He’s floating free.”

White spoke later of his feelings of the moment, “There was absolutely no sensation of falling. There was very little sensation of speed, other than the same type of sensation that we had in the capsule, and I would say it would be very similar to flying over the Earth from about 20,000 feet. You can't actually see the Earth moving underneath you… I think as I stepped out, I thought probably the biggest thing was a feeling of accomplishment of one of the goals of the Gemini IV mission. I think that was probably in my mind. I think that is as close as I can give it to you."

There were some communications problems, but the Cape could hear White through McDivitt’s communication system.

White, “Am I in your view, Jimbo?”

McDivitt, “Well, you know I can’t see…”

White, “Don’t sweat it. I’ll come to you.”

McDivitt, “Ooops – there goes your glove… well, we’ll just let it go.”

White, “All right.”

White, “Okay, I rolled off and I’m rolling to the right now. Under my own influence. There goes a… looks like a thermal glove, Jim.”

McDivitt, “It is, Ed.” …

White, “It really looks funny to see my glove out there, Jim.”

McDivitt, “Does it?”

The glove floats free in this frame from the 16mm movie camera mounted on the hatch. |

Ed White floats away from the spacecraft, attached to his tether. |

Ed White floats beside Gemini IV in the first American EVA. |

White commented later, “I tried to use the gun very sparingly. I just used it enough to satisfy myself that I could make manoeuvres, so in my own mind that I could control myself in both pitch, yaw and translation. If you can control your pitch and yaw and translate fore and aft you can go from point A to point B – the roll isn’t very important. I wasn’t trying to control myself in roll.”

White, “See me yet?”

McDivitt, “No. Sure don’t.”

White, “Huh?… oh, there you are. I can spin around now.”

McDivitt, “Okay. Just a second … you’re right in front, Ed. You look beautiful.”

White, “I feel like a million dollars. All right, we’ll pitch up and yaw left. I’m coming back to you.”

Ed White with the Pacific Ocean near Hawaii as the backdrop. |

Initially McDivitt held the spacecraft steady, but as White began floating around he let it drift. Using his gun, White propelled himself down to the nose of the spacecraft, then back to the adapter end, but soon ran out of fuel, and reported:

“It’s very easy to manoeuvre with the gun. The only problem is I haven't got enough fuel. I've exhausted the fuel now and I was able to manoeuvre myself around the front of the spacecraft, back, and manoeuvre right up to the top of the adapter. Just about … came back into Jim’s view. The only thing I wish I had more fuel. This is the greatest experience I’ve … it’s just tremendous. Right now I’m standing on my head and I’m looking right down and it looks like we’re coming up on the coast of California. I’m going into a slow rotation to the right. There’s absolutely no disorientation associated with it.”

McDivitt observed: “One thing about it, when Ed gets out there and starts wiggling around it sure makes the spacecraft tough to control…”

Ed White’s photo from the nose of Gemini IV. |

Ed White over cloud off the coast of California. |

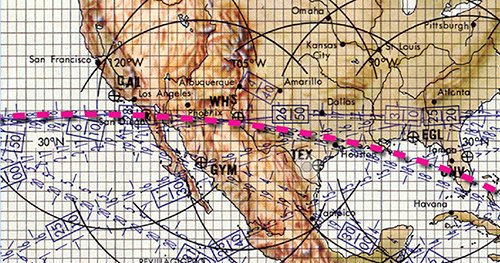

The path Gemini IV took on its third orbit, during Ed White’s EVA is superimposed on this detail from the NASA groundtrack map. Preserved and scanned by Hamish Lindsay, |

White then began to use the umbilical tether to move around. He later recounted,

“The tether was quite useful. I was able to go right back where I started every time, but I wasn’t able to manoeuvre to specific points with it… I also used it to pull myself down to the spacecraft, and at one time I called down and said, ‘I am walking across the top of the spacecraft’ and that is exactly what I was doing. I took the tether to give myself a little friction on the top of the spacecraft and walked about three or four steps until the angle of the tether to the spacecraft got so much that my feet went out from under me. I also realised that our tether was mounted so that it put me exactly where I was told to stay out of.”

Gemini IV has passed over San Diego and is heading towards a point just south of Phoenix, Arizona. To the right in this photo, is California. Visible over Ed White’s left shoulder is the Gulf of California and Baja California. Camera facing SW. |

While McDivitt sat at the controls keeping the spacecraft as steady as possible with its nose pointing down at the bulk of the continental United States spread out below, White moved around while they both took photographs and discussed the view.

Grissom, "Take some pictures."

White, “Okay. I’m going to work on getting some pictures, Jim.”

McDivitt: “Get out in front where I can see you again. I’ve only got about three (pictures) on the Hasselblad. Where are you?”

White, “Right out in front now. I don’t have the control I had any more without the gun.”

McDivitt, “Yes, I noticed that.”

Ed White with the Gulf of California and Baja California behind him. Guaymas Tracking Station is somewhere behind his left knee. From a viewpoint near White Sands, New Mexico. |

In Houston, Flight Director Chris Kraft was beginning to look anxiously at the time. The Flight Plan called for a space walk of 12 minutes, and it was already well past that with no signs of White returning.

Grissom, “You’ve got about five minutes.”

White, “But I want to get out and shoot some good pictures. I’m drifting down under the spacecraft.”

McDivitt, “I’m going to start firing the thrusters now.”

White, “There’s no difficulty in recontacting the spacecraft. It’s all very soft, particularly as long as you move nice and slow. I’m very thankful to have the experience. It’s great, Gus. Right now I’m right on top of the spacecraft – just above Jim’s window. I’ll bring myself in and put myself out of your view, Jim.”

McDivitt, “Okay… hold it and I’ll take your picture.”

White, “Right now I could manoeuvre much better if I didn’t have the gun with the camera on it because I have to tie one hand up with it.”

McDivitt, “Stay right there if you can. Do you want me to manoeuvre for you now, Ed?”

White, “No… I think you’re doing fine. What I’d like to do is get all the way out, Jim, and get a picture of the whole spacecraft. I don’t seem to be doing that.”

McDivitt, “Yes, I had noticed that. You don’t seem to get far enough away.”

White, “No.”

McDivitt, “Where are you now? Am I clear to thrust a little bit?”

White, “No – don’t thrust now.” He didn’t want any accidents from the thruster propellents.

One of Ed White’s photos of the outside of the spacecraft.

McDivitt, “Okay, Ed. Just free-float around. Right now we’re pointing just about straight down at the ground.”

White, “I’m coming back down the spacecraft. I can sit up here and see the whole California coast.”

White, “How you doing old buddy?”

McDivitt, “Pretty good… how about you?”

White, “Good. Looking right in your window.”

McDivitt, “Where? You’re not even there… are you there, Ed?”

White, “No. I’m moving out now.”

An increasingly anxious Grissom, “You’ve got 4 minutes and 30 seconds left.”

White, “Okay, I’m going to free drift and see if I can drift into some good picture taking positions.”

McDivitt, “Ed… smile.”

White, “I’m looking right down your gun barrel. All right.”

McDivitt, “You smeared up my windshield, you dirty dog.”

White, “Well… hand me a Kleenex and I’ll clean it.”

McDivitt, “Ha! See how it’s all smeared up there.”

White, “Yes.”

In this photo of the window, taken after the EVA, the smearing is evident. (The levels have been adjusted in this photo.)

McDivitt, “We’ve been tumbling around. I don’t even know exactly where we are, but it looks like we’re about over Texas. As a matter of fact, you know, that looks like Houston down below us.”

White, “I believe it is, Jim.”

McDivitt, “Gus, this is Jim. Got any message for us?”

Grissom, “Gemini 4 – Get back in.”

McDivitt, “We’re coming over the east now and they want you to come back in now.”

White, “Back in?”

McDivitt, “Back in.”

Grissom, “Roger. We’ve been trying to talk to you for a while here.”

White, “Aw, Cape, let me just find a few pictures.”

McDivitt, “No, back in. Come on.”

White, “Coming in. Listen, you could almost not drag me in, but I’m coming.”

Grissom, “You have 4 minutes till Bermuda LOS (Loss of signal).”

Ed White. S65-30432.

Ed White floats beside Gemini IV in the first American EVA.

McDivitt, “Okay. Okay. Don’t wear yourself out now. Just come on in.”

White, “I’m trying to get a picture of the spacecraft now.”

McDivitt, “Ed, come on in here. Let’s get back here before it gets dark.”

White sighed, “Okay. This is the saddest moment of my life.”

McDivitt, “Well, you’re going to find a sadder one when we have to come down from this whole thing.”

White, “I’m coming.”

McDivitt, “Have you any messages for us Houston?”

Grissom, “Are you getting him back in?”

White's boots thumped on the spacecraft as he reluctantly worked himself to the top of the capsule hatch, handed back the camera, and again stood on the seat. Savouring the moment he stood briefly on the seat, looking at the stunning view of Earth spread out below them.

At 4:50:04 GET (0606:03 AEST) McDivitt announced the end of the spacewalk, “He’s standing on the seat now. His legs are down below the instrument panel.”

Capcom, “Okay. Get him back in. You are going to have Bermuda LOS in about 20 seconds.”

End of the EVA.

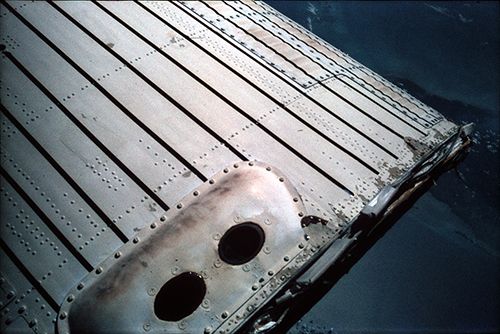

After White struggled to get back into his seat in the spacecraft they closed the hatch and grabbed the ratchet handle to secure it. To White’s shock it failed to catch, so the fastenings had to be manoeuvred into place by hand and secured, McDivitt trying to hold him down in the seat. Throughout the EVA the hatch seal had been exposed to the vacuum of space, and the intense cold had stiffened the seal material making it extremely difficult to close tightly.

McDivitt explained what happened with the hatch from his point of view to the Houston Capcom,

“As he got back into the spacecraft, we had a considerable amount of difficulty with the hatch. First we lifted the ratchet portion of the hatch to engage. After we got that engaged, we couldn’t get the hatch closed down far enough. Actually we started pulling down on the locking handles to get the dogs out. So, we had a rather exciting time.

It went on for – I think we were 44 minutes after we started the EVA. I was looking at my event timer, which I had started when Ed exited the spacecraft. At 44 minutes we still didn’t have the hatch closed. We were trying to take things calm, cool and collected so we didn’t get things all screwed up. Finally, by my pulling as hard as I could to get the hatch-closing device, and Ed pulling down as best he could we were able to force him down into the seat and get the hatch closed fully. Ed seemed to be up much higher today than he had been in any of our zero-g EVA’s in the airplane.”

White, “I don’t believe we were actually having difficulties with my head clearance. I felt like I had plenty of head clearance and I could actually reach down and manipulate the dogs. We just seemed to have a little more effort in closing than we have ever experienced before.”

They both collapsed back into their couches, physically exhausted, with sweat streaming into their eyes, and fogging their faceplates. White became so overheated from the struggle to get back in it took him a few hours to return to normal. The EVA equipment was supposed to be dumped out in space to give the astronauts more room in the cramped cabin, but the hatch was never opened again, so all the EVA suits and associated gear had to be carried around for the rest of the mission.

White had been outside the spacecraft for an exhilarating 21 minutes.

Ed White during his EVA. |

After they settled down out of range of any tracking station, we pick up their conversation off the on-board tape recorder, White saying,

“That was something. That was the most natural feeling, Jim.”

McDivitt, “Yeah, I know it. You looked like you were in your mother’s womb.”

McDivitt then asked, “You get the flight plan out and see who we can talk to.”

Mcdivitt announced the time, “Five fifteen.”

White, “Shoot. We don’t talk to anybody until we get to Carnarvon at 5:35?”McDivitt called into the ether, there being no tracking station within range,

“Gemini 4 transmitting into the blind. We’re back in, the cabin’s resealed, We’re all set and all safe. We’re going to do a delayed tape time playback over Carnarvon at about 5:35… just about 13 minutes.”

White, “We’re starting to get cleaned up, Jim.”

McDivitt, “Yes, we are. One thing, Ed. Just be slow, cautious and thorough.”

White, “Roger. I’m slow…”

McDivitt, “I know you are. I’m amazed. I never thought I would see the day you would be so slow.”

They began discussing the hatch problem, in particular the pre-mission training.

White, “You know that was just… we rehearsed this so many times.”

McDivitt, “Boy, it really paid off.”

White, “It’s paid. Big dividends.”

McDivitt, “As a matter of fact I think I’m going to tell Chris (Kraft) that on the radio.”

White, “Don’t alarm them.”

McDivitt, “No. I’m just going to tell them that training just paid off. We could get the hatch closed. You knew how hard you could hit it without hurting it.”

A little later McDivitt mused, “I tell you the day side just isn’t long enough for EVAs. You know that?”

White, “No. You have to go like gangbusters.”

Carnarvon Fourth Pass.

Gemini IV came up over our horizon at Carnarvon at 5:32:04 GET (0648:03 AEST), the crew anxious to tell somebody about their status. It had been an exciting long night and early morning for us on the ground.

Author, “I had 20 centimetre speakers to listen to the astronauts’ voices, and will always remember clearly sensing the tension and excitement in their voices as well as the atmosphere of the confined cabin that came through those speakers.”

Author Hamish Lindsay at the Gemini voice receivers. |

McDivitt: “Carnarvon. Carnarvon. Gemini 4.”

Fendell: “Gemini 4… Gemini 4… this is Carnarvon Capcom.”

McDivitt: “Gemini 4. I read you loud and clear. It’s nice to have somebody to talk to again.”

Fendell: “Roger it’s good to hear you. How are thing’s going?”

McDivitt: “Okay. We’re back inside the spacecraft; we are repressurised to 5 psi. We are not – I say again, we are not, going to depressurise the spacecraft again.”

Fendell: “Roger. Understand. How are you feeling?”

McDivitt, “Everybody’s fine… we’re feeling great.”

Fendell, “Roger. Can you give me battery readouts please?”

And the rest of the pass over Carnarvon followed a technical exchange on updates and spacecraft status, with not a word about the big event just experienced. Discussions about the event began over Hawaii.

Recording starts at acquisition at 05:31:50 GET. 3.6MB mp3 file, 6 minutes 54 seconds. Tape recorded and preserved by Hamish Lindsay. |

White tells of his spacewalk experiences.

At 5:59:29 GET (0715:28 AEST) over Hawaii White began to talk about his experience,

“While I was outside I noticed on Jim’s window – he’s got a coating on the outside of it. One time when I brushed up against it with either my shoulder or arm it actually smeared right over on it, and it smeared the upper part of his window so he couldn’t see out. When I look out from this side, I can see that it is rather heavily coated with some type of material. When I was outside looking in it looked like a … it looked like almost a greasy film on the outside of it. My window doesn’t seem to have so much on it.”

Six minutes later White continued,

“The tether – the location of the tether, or the umbilical restraint on the outside hatch made it rather difficult to do any EVA work as far as from tether aerodynamics out in front of the spacecraft. Whenever I operated in that area the tether would… when it would come to its end would start me back and the reaction would carry me back up towards the… over the spacecraft and back towards the adapter section. That’s why I kept going out of sight during my manoeuvring out there up above the windows, and then drifting back towards the back of the spacecraft. I had to continually keep pulling myself to get out in the front of the spacecraft.

I wasn’t satisfied with the pictures I was getting. It was rather difficult to keep any of the lanyards that I had on… I had the lanyard on the gun and the tether and umbilical that I was on and several other miscellaneous type lanyards flailing around and it was difficult to keep them from in front of the camera lens. I kept trying to move them out of the way so I could take a picture. I’d say they were in front of me probably 50 or 60 per cent of the time and the other percent of the time I was not in a good position as I would like to be. I think I took in the neighbourhood of a dozen pictures.

I felt no tendency to bang into the spacecraft. I was able to approach the spacecraft just about from any attitude I came back in.

There was no disorientation whatever. I felt that I could either look down at the ground – I felt perfectly at home looking down at it – and I could roll around on my back and look up and it was not disorienting me in any way. The spacecraft was my best reference. Any time I saw it I immediately had a good reference and, in fact, at times near the end I was using my tether and actually walking up and down on the surface of the spacecraft, using it to hold me down as an anchor.”

At 6:19:31 GET (0735:30 AEST) Grissom summarized the moment,

“Looks like we won one after all!”

McDivitt, “Ha! Ha!”

At 7:35:40 GET, nearly 5 pm spacecraft time, (0851:39 AEST) over Hawaii, White began to think of getting some sleep,

“Bacon and egg bites, toast and orange juice, and I’m about to go to sleep.”

Ed White onboard Gemini IV during the mission. |

He managed to get about 4½ hours of restless sleep.

At 17:24:35 GET (1840:34 AEST) over the ship Rose Knot Victor off the west coast of Peru in South America Houston wondered how the astronauts were getting on with all the EVA clobber they weren’t able to dump into space.

RKV Capcom asked,

“Gemini IV, Flight asks how you are doing at getting things stowed away and if you are getting a little crowded up there?”

McDivitt, “Indeed we are crowded. We have got most of that junk down in the foot well, and I guess we are going to have to hold some of it during reentry.”

Capcom, “Oh Boy – that sounds like a lot of fun.”

McDivitt, “We are trying to figure out what to do with all the stuff we’ve got.”

Capcom, “Well, let’s see – there’s a lot of empty space up there around you.”

McDivitt, “Yes, and I sure wish we could get to it.”Houston Capcom Gene Cernan then asked, “You might ask him to go briefly over the trouble he had closing the hatch.”

RKV Capcom, “Flight advises they have good communications on this air-to-ground remoting – and would like you to go over the problems you had with the hatch closure.”

McDivitt, “Roger. There are two gears that we have that go around when you pull the handle back and forth. One of them is the gear that sort of acts as a ratchet – a little cylinder with a piston in it and a spike behind it that engages the ratchet. We were having a little trouble with that before we got it (the hatch) open and after we got it open we had difficulty getting this ratchet to work.

Also we had a great deal of difficulty in getting the hatch to close far enough so we could even start latching it. Then Ed had to push the ratchet in with his hand on every go until it started. And I was pulling on the thing until I thought I was probably going to break a lug right out of the hatch. We finally got it going, and it finally came forward. So I don’t think we ought to try opening it up any more.”

Capcom, “Roger. Sounds like a good idea to keep it closed.”

At 22:15:23 GET (2331:22 AEST) Houston Capcom Gus Grissom read up the newspapers headlines about their EVA, and White responded,

“It was tough to get in, real tough to get back in. That was sure something out there. Were ya’ll reading us? We never knew when ya’ll were reading us or not.”

Grissom, “Yeah, your VOX (voice operated microphone) was keyed all the time … we couldn’t get in or try and tell you that your time was up and to get back in. Never could get through to you at all.”

White, “Oh is that right? I’m glad you didn’t.

Grissom, “Yeah – I could tell that.”

A few minutes later Grissom suddenly asked,

“Hey, Ed, you were talking about walking on the spacecraft – were you actually walking on it?”

White, “Yes, I was. I was using the tether to pull myself down towards the spacecraft and I was right on top of it. The next time I get into a tether type of operation it looks pretty good but is still hard to get any traction on the top. But if you pull yourself down you can get a little bit.”

Grissom, “You forgot your magnets, I guess.”

At 66:29:10 GET (1945:09 AEST 6 June) over Corpus Christie,Texas, Capcom Grissom asked the pilots,“Gemini 4, Houston. Can you give us any idea of where you’ve got some of your gear stored? We’re concerned about CG (centre of gravity), Over.”

McDivitt, “It looks like we’re going to end up with ECM on the floor, and we’re going to have the cable in Ed’s lap. And we’re going to have the gun stowed in the centre food box where it was. We’re going to have the film in the centre food box. We’re going to have the camera equipment in the side food box.”

Grissom, “Roger – we got it.”

Then, just after passing over Carnarvon, at 67:40:52 GET (2056:51 AEST) 6 June the crew saw a shooting star enter the atmosphere below them, White,

“I just saw a falling star trail down not too far in front of us and it burned out considerably below us. The whole tail was quite long, which was actually below our level. It burned up considerably below us.”

McDivitt, “Yes.”

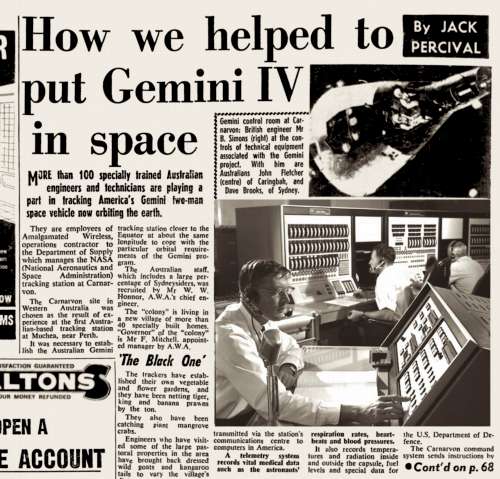

Carnarvon’s role was featured in Sydney’s Sun-Herald newspaper on 6th June 1965. The paper used a photo by Hamish Lindsay. (A scan of his original has been substituted here.) |

Melbourne, Australia, turns on its lights for Gemini IV.

After that frantic start, the rest of the mission was much quieter. On the 44th orbit the city of Melbourne, in Victoria, Australia, turned its lights on for the astronauts.

At 68:43:28 GET (2159:27 AEST) on 6 June, two days into the mission, Carnarvon Capcom Ed Fendell called up,

“I’d like you to take a look to see if you can see the lights of Melbourne. That’ll be about 8 minutes from now.”

McDivitt, “Okay. At 00:08?”

Fendell, “Ought to be a pretty good time. They should be just a little to the right of you – just about underneath you – just slightly down.”

McDivitt, “Okay. To the North?”

Fendell, “Negative. To the south.”

McDivitt, “To the south. Okay.”

Fendell, “I don’t know whether you will see it. It’s raining here real bad. I don’t now whether the weather is clear over Melbourne, or not.”

McDivitt, “Yes, every time I go over Australia all I ever see is thunderstorms.”

Fendell, “Had three inches today.”

McDivitt, “Wow!”

Fendell, “They need it.”

McDivitt, “Do they need it all in one day?”

Just over 6 minutes later McDivitt called back,

“I see some lights shining on the clouds down below me at this time.”

Fendell, “All right. That should be Melbourne.”

McDivitt, “Okay. Very good. Tell them I thank them for lighting the night for me.”

Fendell, “Very good. They’ll appreciate that.”

McDivitt, “Tell them the next time, though, to get those clouds out of the way so I can see the city, and not just the clouds.”

Fendell, “That’s the same way I feel. I’m all miffed.”

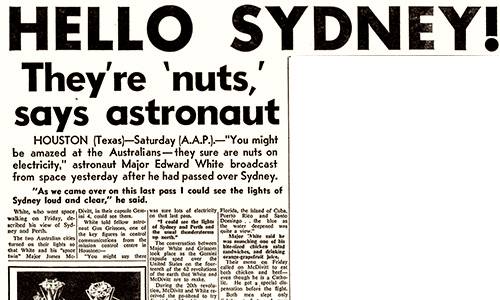

While Melbourne was under cloud, McDivitt and White had seen Perth and Sydney clearly on their 14th orbit. Article from the Sydney Sun-Herald newspaper, page 2, 6th June 1965. |

Towards the end of the mission, at 75 hours into the flight, the spacecraft computer was updated and McDivitt was told to turn the computer off. But he found he couldn’t, and after much analyzing and attempts the computer quit completely, so instead of coming back under control of the astronauts, the spacecraft had to make a ballistic reentry, which meant that the capsule would behave more like a projectile, instead of a spacecraft under control doing a lifting bank angle re-entry. As they rolled in, they saw their just discarded adapter (the unit attached to the back carrying the power units and consumables) trailing behind, turn into an orange mushroom as it burned its way back into the thickening atmosphere.

Splashdown.

At 3,230 metres the main parachute burst out and the two astronauts braced themselves for the 1,500 metre two-point suspension mark when the Gemini III crew were flung forward to crack their helmets on the windows. This time the crew lurched forward, but neither knocked their helmets against anything.

The recovery ship, the carrier USS Wasp, had to move 238 kilometres to the west of the original position, to accommodate this change. Gemini IV dropped into the Atlantic 81.4 kilometres from the target at midday (12:12 pm USEST) on Monday 7 June (0312:11 AEST 8 June 1965) watched by one of the recovery helicopters.

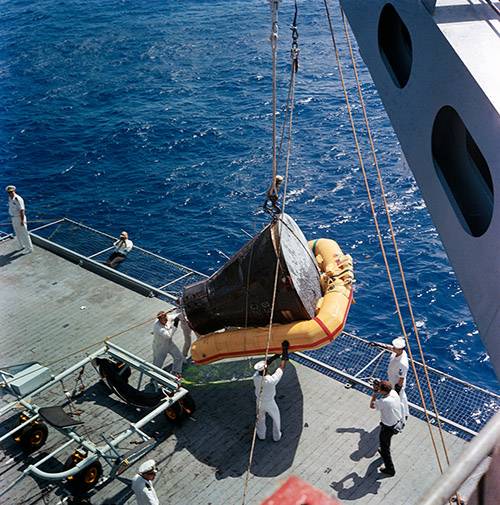

The Gemini IV capsule is lowered onto the deck of the USS Wasp. |

Ed White and Jim McDivitt on the deck of the USS Wasp. |

Gemini IV went around the Earth 66 times in just over 4 days, covering a distance of 2,590,561 kilometres.

Summary.

This mission was declared a great success, the doctors were elated, and the critics who predicted that the astronaut would become unconscious, experience vertigo, or disorientation as soon as he stepped out of the spacecraft were silenced. White said that his desire to do strenuous work, such as using the exerciser, dropped as the flight progressed. McDivitt reckoned this was probably due to lack of proper sleep due to the disturbances from the companion’s activities. They should have slept at the same time instead of alternately. It was a good thing they did the spacewalk at the very beginning of the flight when everyone was fresh.

All the systems, computers and procedures in the new Mission Control in Houston had worked to perfection.

And the Americans had caught up with the Russians.

The Gemini IV capsule is now on display in the entrance foyer of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington – alongside Friendship 7, the Apollo 11 Command Module Columbia, and beneath The Spirit of St. Louis. |

See also: Gemini IV audio recorded at Carnarvon. |

References:

Tracking Apollo to the Moon by Hamish Lindsay.

Carnarvon and Apollo by Paul Dench and Alison Gregg.

Failure is not an Option by Gene Kranz.

A Walk in Space. NASA booklet. US Government publication. No author or date.

On the Shoulders of Titans: A history of Project Gemini by Barton Hacker & James Grimwood. NASA SP-4203.

NASA websites.

Onboard images courtesy Arizona State University School of Earth and Space Exploration’s March to the Moon Image Gallery.

Unless stated, all images are NASA photos.

Quotes from Ed Fendell: 2012 e-mail to Colin Mackellar, used with permission.

Images and audio selected and processed by Colin Mackellar.