Gus Grissom and John Young. NASA photo.

Gemini III

The first Gemini manned flight.

24 March 1965

NASA PREPARES FOR THE GEMINI MANNED FLIGHTS.

The Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland had organised a team of operational and engineering people to fly to the tracking stations around the world and train them all to the same standard, and also to evaluate their performance. So the first major event for the world wide tracking network (including us at Carnarvon), was a visit from this simulation test team and a Super Constellation aircraft. While the aircraft flew back and forth over the station behaving like a spacecraft, the ground team put the station operational staff through searching exercises to train them in the procedures to follow when the real mission was in progress. Carnarvon was the first station ready, so the brand new Gemini procedures were first tried out at Carnarvon.

The Gemini Program began with Gemini Launch Test GLV-1 flight on 8 April 1964 to test the performance of the launch vehicle. The mission was terminated after three orbits with all objectives achieved, while the spacecraft flew on for 64 orbits over 3½ days before disintegrating in the atmosphere.

After delays because of unfavourable weather, including Hurricanes Cleo and Dora, the second Gemini launch test, called GLV-2, left pad 19 on January 19 1965. To check its integrity, the spacecraft with a dummy crew was hurled 159 kilometres above the South Atlantic, to scorch back in to reach a temperature hotter than any mission so far. Picked up by the USS Lake Champlain after its 19 minute sub-orbital flight, the engineers found the spacecraft and its contents in good shape. Modifications to the Titan rocket’s fuel distribution system dampened the violent oscillations that had been experienced just after launch, so now Gemini was ready to fly man.

The first mission was planned to be Gemini III, with Gus Grissom and John Young.

The crew.

Originally Deke Slayton had chosen Alan Shepard to command this flight with Tom Stafford as Pilot, but in May 1963 Shepard went down with Ménière's Syndrome; excessive fluid pressure in his left inner ear which caused dizziness, ringing, vomiting, and sometimes dropped him to the floor. So he was grounded, and joined Slayton organising the astronaut corps, but determined to get back on flight status as soon as possible. He became somewhat moody and unpredictable and became known as the Icy Commander or Smilin’ Al according to his mood. Gaye Alford, his secretary, would warn callers which mood to expect by hanging either a scowling picture or a cheerful portrait outside his door.

Slayton announced that Gus Grissom would command Gemini III, with John Young as his pilot just after the GLV-1 trial flight was declared a success.

Gus Grissom and John Young. NASA photo. |

Virgil Ivan “Gus” Grissom. Aged 38 for this flight, Grissom was born on 3 April 1926 in the small town of Mitchell, Indiana. He graduated from the Mitchell High School and received a BSc. in Mechanical Engineering from Purdue University. In 1952 he flew 100 combat missions in Korea. I

n April 1959 he was selected as one of the original Mercury 7 astronauts. He was the second American to fly in space in a 15 minute sub-orbital flight in the Mercury Project. He nearly drowned when the hatch blew off his spacecraft after landing, and he had to swim for his life. The rescue team were busy trying to salvage the spacecraft before it sank, and ignored the frantically waving, sinking astronaut; luckily he was rescued in the nick of time by a helicopter that spotted his predicament. This Gemini flight made him the first astronaut to fly in space twice. He logged more than 4,600 flying time, 3500 of them in jets. He was tragically killed in the Apollo 1 fire on 27 January 1967.

John Watts Young. Aged 34 years for this flight, Young was born on 24 September 1930 in San Francisco. He attended Orlando High School, Florida, and received his BSc. in aeronautical engineering with highest honours from Georgia Institute of Technology in 1952. He was a naval officer, serving on a destroyer in the Korean War, a test pilot and aeronautical engineer.

From Gemini III he went on to the longest career of any astronaut, with two Gemini missions, twice to the Moon in Apollo and two Shuttle flights. He was Chief of the Astronaut Office from 1974 to 1987. He retired from NASA in December 2004. Young has logged more than 15,000 hours flying time in props, jets, helicopters, rocket jets, and his six space flights totalled 835 hours.

Gemini III’s Call sign Molly Brown.

Following his near drowning episode in the second Mercury manned flight, Grissom was granted permission to call his spacecraft Molly Brown after a Titanic lady survivor and the stage show “The Unsinkable Molly Brown”. Grissom’s spacecraft was the first and last one to be named in the Gemini Program. NASA officials were aghast at the choice of name, saying it lacked dignity, but when they heard his second choice was Titanic they promptly agreed to Molly Brown.

The brawl between the astronauts and the Flight Control team for control of Carnarvon.

At Carnarvon this mission began a brawl between the astronauts and the Flight Control Team leaders for the position of being in charge of running the mission at remote sites. Traditionally in Mercury the Capcom in charge of the flight control team had been an astronaut, and in this case Pete Conrad was sent to Carnarvon as the astronaut, and he understood from Deke Slayton he would be in charge of the mission as the Capcom. But Danny Hunter, the Flight Team Leader had instructions from Gene Kranz putting him in charge as the Capcom. The impact of this conflict on us was confusion whose orders we should follow. We, mainly the Telemetry and Communications sections setting up the Capcom’s console, were bewildered by conflicting instructions given by the two ‘leaders’, both insisting they were the boss. It was a bitter struggle.

Paul Dench recalls: “I remember it all very well as I was the person probably most affected by the conflict. I was constantly having to change the configuration of the CapCom console from the common network configuration as required by Danny Hunter to a very different configuration required by Pete Conrad. I was a nervous wreck until Lewis Wainwright promised he was sorting it out with Mission Control.” – e-mail to Colin Mackellar, 29 October 2008. Photo: The Gemini Capcom and engineering consoles. M&O Dick Simons in the foreground. Photo: Hamish Lindsay. (See also Hamish’s full set of Carnarvon photos.) |

The argument went all the way to the top. Gene Kranz had just gone to bed at around 2:30 am when there was a banging on his door. Outside it was Chief of the Astronauts Deke Slayton with the Mission Flight Director Chris Kraft in a heated argument, with Slayton shouting, “Dammit, Chris, get your guy (Hunter) under control.” Kranz realized that this was a battle over who was in charge at Carnarvon. It seemed that Hunter told Conrad that Kranz had put him in charge and … “if you give me any more trouble, I want your ass out of the control room.” Conrad seethed at this confrontation, as he had been told by Slayton that he was in charge.

Kranz called Hunter the next morning and was told that Conrad had taken over, and the station staff wanted to know who to take orders from, “If Carnarvon wants to support the mission, they damned well better take their orders from me. The site staff want a teletype directive to cover their ass.”

Kranz drafted a message that put Hunter in charge, but Slayton disagreed, “If we aren’t going to put my astronauts in charge, it is a waste to send them.” So Kraft tried to sort out the dilemma by ordering Hunter in charge of the station’s operations and Conrad as Capcom during mission real time. This instruction was issued to Carnarvon and Hawaii, where Neil Armstrong was in a similar position.

A day before the launch of Gemini III Kraft held a briefing embracing the world-wide tracking network. At the end Hunter came on line and wanted to know how to understand Kraft’s instruction. He said that the message did not resolve anything and he was going to hang it in his crapper when he got back home.

Incensed at this insult, Kraft curtly told him he had his orders. This publicly aired clash, heard around the world, introduced a lot of friction between the astronauts and the ground controllers for a while.

So Conrad was our Capcom for Gemini III.

Danny Hunter was moved sideways and became the Station Director at the Madrid Tracking Station. But the outcome of the fracas was Gemini III was the last time an astronaut communicated with the spacecraft during the Gemini Program at Carnarvon. Of course in Apollo the missions were run from Houston, there were no Americans on site during the missions.

Gemini III gets under way.

The flight control teams spread around the world. Led by Danny Hunter, the team to conduct the mission from the Carnarvon station arrived and lodged at the local hotels.

The Capcom was astronaut Pete Conrad, later to walk on the moon in Apollo 12. He recalled to me:

“I remember flying in to Carnarvon the first time on MacRobertson Miller Airlines and the chap coming back and opening up the door and throwing my bags out on the red dirt and saying, ‘See you on the way back, mate,’ and off they went. That was at the end of about 54 hours of travelling.

I checked into the hotel and asked the girl behind the desk did she have a reservation for a Lieutenant Commander Conrad? She said, ‘Upstairs on the second floor; take the first room that’s made up and let me know the number on the way out!’”

GEMINI III - THE FIRST MANNED GEMINI FLIGHT.

Fact box: |

|

| Gemini Spacecraft No. 3 Callsign: Molly Brown |

|

Crew: Backup crew: |

|

| Launch | 1424:00 UT 0924:00 USEST Tuesday 23 March 1965 (0024 AEST Wednesday 24 March 1965) |

| Splashdown | 1916:31 UT Tuesday 23 March 1965 (0516:31 AEST 24 March 1965) |

| Splashdown location | 22° 26’N by 70° 51’W |

| Mission duration | 4 hours 52 minutes 31 seconds. |

| Inclination | 32.6° |

| Orbits | 3 orbits |

| Apogee | 224.2 kilometres |

| Perigee | 161.2 kilometres. |

| Period | 88.3 minutes |

| Total distance travelled | 128,748 kilometres |

| Spacecraft mass | 3,236.9 kilograms |

On launch day the daily afternoon sea breeze was blowing steadily over Carnarvon as the station staff were picked up by the little gray Commer buses dashing among the houses, and driven up to sunbaked Brown's Range. In the main T & C (Telemetry and Control) building, we escaped from the heat and sand outside, first grabbing a cup of tea or coffee and cooling off in the refreshing air-conditioning before spreading among the equipment to begin running through the final checklists.

Grissom and Young were woken up 0440 local time in the crews’ quarters on nearby Merrit Island. After a breakfast of Porterhouse steak and scrambled eggs, they were driven out to the astronaut ‘ready room’ in a two-car motorcade. Arriving at 0600 am. they suited up and by 0705 were heading for launch Pad 19. Grissom followed Young to the elevator and they were whisked up to the 11th level.

The crew entered the capsule ahead of schedule at 0712, with the count at T-103 and counting. Tracking stations around the world were ‘green,’ ready to support.

The hatch was closed at 7:34am.

The count was held at T-35 minutes for a leaking oxidizer line. Technicians tightened the valve coupling and with the erector lowered, the count proceeded to a lift-off. The count was ahead of schedule by about 20 minutes, and Young complained about all that extra time spent lying on their backs, just waiting. The overcast weather cleared just in time for the launch.

Launch

At Carnarvon, Operations Supervisor Dick Simons sat down at the Operations Console, and began to bring the station together over the intercom.

Author:

“We all settled down to our mission stations and listened to the countdown on our headsets. This was our first real mission, a great moment after the many months of preparation. While I was double checking all the settings I was surprised to receive an order from Capcom Conrad to tune in to the short wave Voice of America, to give him the launch description in real time. The Voice of America fed us a continuous stream of information in great detail, much more than the occasional brief comment down our private SCAMA phone line from the Cape. As I had to use a mission radio receiver, the moment the spacecraft was off the ground I had to switch back to mission configuration.

At last we heard Cape Capcom Gordon Cooper say, “You’re on your way, Molly Brown.”

Grissom responded with: “Yeah, man.”

Gemini III is launched on March 23 (US time) 1965. |

A Titan II GLV booster sent Gemini III into orbit from pad 19 at Cape Canaveral. Within 60 seconds the vehicle was speeding upwards at 1,059 kilometres per hour, the crew pulling 2gs. By 2 minutes, still on the main Titan booster, they were travelling at 4,828 kilometres per hour. After staging at 02:35:00, when the big Titan booster dropped off, they increased speed to 10,460 kilometres per hour on the second stage. At 4 minutes 35 seconds they were travelling at 19,300 kilometres per hour and pulling 3.5gs. At 5½ minutes the second stage shut down and explosive bolts severed the second stage from the spacecraft. Grissom then fired the aft thrusters to kick them into an initial orbit of 122 by 175 kilometres.

At 0:37:18 GET over Africa Grissom noticed, “There is lightning out there.”

Young, “Yep.”

Grissom, “Look at that stuff going by. Oh, boy! Really does sparkle doesn’t it?”

Young, “Yes. There’s the Southern Cross and Alpha and Beta Centauri.”

Carnarvon’s first pass.

Our first pass was at 0:50:27 GET (0114:27 AEST). After a technical discussion Grissom said, “I believe I see a light from Perth.”

Conrad, “Roger. I understand you see a light from Perth. We’ll have a radiator status….”

|

370kb mp3 file, 36 seconds. With thanks to Terry Kierans’ CROTrak. |

First orbit change of a manned spacecraft.

At 1:33:00 GET (0157:00 AEST) during the first pass over Corpus Christi, Texas, Grissom fired two 38.5 kilogram rockets of the Orbit Attitude and Manoeuvring System (OAMS) for 74 seconds to slow Molly Brown down by 15.5 metres/second and drop it down into a nearly circular orbit. This was the first orbital manoeuvre by any manned spacecraft.

Texas Capcom, “Texas standing by for your manoeuvre.”

Young, “Do you want me to give Texas a mark when you start burning?”

Grissom, “I will. Twenty seconds to burn. You got that Texas?”

Grissom, “Three seconds.”

Grissom, “Mark.”

Young, “Okay. They appear to be firing good.”

Capcom, “Roger. Texas confirms OAMS thruster firing.”

Grissom, “A bolt just stuck up against the instrument panel. How much time to go?”

Capcom, “Molly Brown, how are your attitudes holding?”

Grissom, “Perfect.”

Young, “Mark. 44 seconds to go.”

Grissom, “They sure burp a lot, don’t they? That may be attitude thrusters though. Probably what it is.”

Young, “Okay.”

Young, “Coming up on one minute…….Mark.”

Grissom, “7 feet per second to go.”

Young, “A minute…… five.”

Grissom, “What did we do? Burn down….give me a mark.”

Young, “Okay…… 4…. 3…. 2….1….Mark.”

Grissom, “Thrusting complete.”

Capcom, “Roger. Confirmed manoeuvre complete.”

Young, “That burn was one minute and fourteen seconds by our watches.”

A first for a manned spacecraft. "That was a big event, really a big event," Grissom said later.

That corned beef sandwich.

Another event which seemed minor but became big with repercussions reverberating all the way up to Congress, was John Young’s corned beef sandwich from Wolfie’s delicatessen at Cocoa Beach. The back-up Commander Wally Schirra had given it to him.

Schirra confessed that Young had mentioned there was no meal scheduled for the five hour flight, and if you added the 2½ hour countdown, he thought they were bound to get hungry, “So I went to Wolfie’s restaurant in Cocoa Beach and bought a corned beef sandwich on rye with two dill pickle slices. I kept it in a refrigerator in the crew’s quarters and got word to Young it was there.”

At 1:52:26 GET (0216:26 AEST) the discussion from the on-board tape recorder,

Grissom “What is it?”

Young, “Corned beef sandwich.”

Grissom, “Where did that come from?”

Young, “I brought it with me. Let’s see how it tastes. Smells, doesn’t it?”

Grissom took a couple of bites, “It’s breaking up. I’m going to stick it in my pocket.”

Young, “Is it? It was a thought anyway.”

Grissom, “Yep.”

Young, “Not a very good one.”

Grissom, “Pretty good though – if it would just hold together.”

Young, “Want some chicken leg?”

Grissom, “No, you handle that.”

Four minutes later they tried the official snack.

Grissom, “How do you like this going backwards? You can tell you’re going backwards, can’t you.”

Young, “Never a doubt. That’s not bad for apple sauce.”

Grissom, “I’ll take a bite of apple sauce – if you don’t eat it all.”

Young, “It’s getting tough to squeeze it out of there.”

Grissom, “If we had some pork chops to go with it, we’d be all right.”

Young, “Yes.”

Grissom, “Here it is back.”

Young told me “It was no big deal – I had this sandwich in my suit pocket. The horizon sensors weren’t workin’ right so I gave this sandwich to Gus so he could relax – there was nothing he could do in the dark to make that thing work, until we got back into the daylight.”

Others didn’t have Young’s view. “It negated the flight’s protocol,” thundered the doctors. “The crumbs could have got into the equipment,” complained the engineers. “NASA has lost control of the astronaut group,” boomed hostile voices around the floor of Congress. The result was a tighter control over what astronauts could take into space. Grissom later admitted that the sandwich was one of the highlights of the mission for him.

Going over Africa the crew were told to look out for the second stage Titan II booster. The spacecraft was in the dark but the booster should be in daylight. It should have been 37 kilometres below and behind them. Unfortunately they were facing the wrong way at the time so never saw it. Their change in orbit meant they were actually passing under the booster.

At 2:17:00 GET (0241:00 AEST), over the ship Coastal Sentry Quebec (CSQ) in the Indian Ocean, they performed a translational burn of 10 feet per second to change their flight path slightly to result in their landing some 55 to 74 kilometres north of their present trajectory landing target. A slight leak of ¼° per second in the yaw thruster caused comment but was not regarded as a significant problem.

The Coastal Sentry Quebec (CSQ), from a NASA film. |

Carnarvon’s second Pass.

On the second pass over Carnarvon we temporarily lost contact with Mission Control at the Cape for about ten minutes. At 2:23:25 GET (0247:25 AEST) Gemini III hove over our Indian Ocean horizon and straight into a blood pressure reading on Young.

Conrad, “We’d like to get a blood pressure on the co-pilot please, and could I have your status?”

Grissom, “Okay, blood pressure coming up and our status is ‘green.’

Conrad, “Very good – we don’t have any communication with the Cape at this time……..”Conrad towards the end of the pass, “You’ll probably go over the hill, Gus. You look good here on the ground. We’ll see you on your next go.”

Grissom, “Roger, thanks, Pete.”

|

1.1MB mp3 file, 2 minutes, 09 seconds. With thanks to Terry Kierans’ CROTrak. |

At 2:53:41 GET (0317:41 AEST) Neil Armstrong, Capcom at Hawaii, confirmed that Gemini III was going to go on to a third orbit,

“Molly Brown Hawaii Capcom. Everything looks good on the ground. We will see you on the next time around. Aloha.”

In the third orbit Grissom completed a fail-safe plan with a 2½ minute OAMS burn that dropped the spacecraft perigee to 72 kilometres to make sure of reentry even if the retro-rockets failed to work. This was added to the flight plan to protect the Gemini 3 crew against being stranded in space in case of a failure of the retro rockets, prompted by Martin Caidin's movie "Marooned".

Cape Retro, and then Cape Flight (Chris Kraft) call Capcom Pete Conrad at Carnarvon and then the Capcom on the CSQ (Coastal Sentry) in the Indian Ocean with news of the retro-fire preparations for re-entry. 4.3MB mp3 file, 8 minutes 50 seconds. Recorded at Carnarvon. Tape recorded and preserved by Hamish Lindsay. Digitised and edited by Colin Mackellar. |

starting at 03:48:00 GET, 18:11:48 GMT (04:11 AEST). Coastal Sentry Quebec has the first communications with Gemini 3 in just over 30 minutes. Recording starts at acquisition. The audio quality is poor because CSQ (and RKV, for that matter) are linked into the Network via HF radio. 2.4MB mp3 file, 4 minutes 45 seconds. Recorded at Carnarvon. Tape recorded and preserved by Hamish Lindsay. Digitised and edited by Colin Mackellar. |

Carnarvon’s third pass.

At 3:56:00 GET (0420:00 AEST) we had our last pass. In the middle of the technical exchanges Conrad called,

“If you are looking at the ground, Molly Brown, Carnarvon has a big bonfire going for you down here.”

Grissom, “We are blunt end forward. We can’t see them yet.”

As there was no further mention of the fire, it would seem they did not see it.

Coming to the end of the mission Young reported the spacecraft still had 55% of its fuel on board, which rated high approval from the systems flight controllers.

At the end of the pass Conrad asked,

“Okay, Gus. I only have one question for you before you go out of range. How’s the flying up there?”

Grissom, “Great.”Conrad, “Fine GT-3. See you next trip – next year.”

in preparations for Re-entry on Orbit 3 – starting at 04:06 GET, 18:29:28 GMT (04:11 AEST). Cape Flight (Chris Kraft) asks Goddard Voice Control to connect him to Hawaii, the tracking ship Rose Knot Victor (RKV), and Guyamas. Communications problems give a feel for the difficulty of running of a global network in the days before satellite and fibre-optic links. Neil Armstrong (Hawaii Capcom) is heard from 01:55 into this recording. 5.9MB mp3 file, 12 minutes. Recorded at Carnarvon. Tape recorded and preserved by Hamish Lindsay. Digitised and edited by Colin Mackellar. |

Retrofire.

Approaching the Californian coast, over the ship Rose Knot Victor (RKV), Young cast off the adapter at 4:32:29 GET (0456:29 (AEST) and at 4:33:13 GET (0445:23 AEST) initiated the retro-fire sequence. One after another the four retro-rockets fired and burned themselves out to bring Gemini III down.

RKV Capcom, “…..5....4….3…2….1 ….Retrofire!”

Grissom, “Auto-retro.”

Capcom, “Manual-retro.

Rocket 3

Rocket 2”

Grissom, “Three of them.”

Capcom, “Rocket 4. Molly Brown, do you confirm all rockets firing normally?”

Grissom, “All rockets fired normally and attitudes were right in the centre.”

Then sensors indicated that Molly Brown was off course, and would miss its target by 69 kilometres, and Grissom’s best efforts to correct their trajectory had no effect.

Grissom, “That was the end of the burn.”

Capcom, “Okay. And how did your attitudes look?”

Grissom, “Attitudes were right on.”

With the main parachute blossoming out at 4:48:40 GET (0512:40 AEST) the success of the mission was sealed.

starting at 04:41:48 GET (05:05 AEST, 03:05 WAST 24 March 1965) covers a ‘Communications experiment’ during re-entry, as well as splashdown. Capcom is Gordon Cooper. The quality of the recording reflects what was heard at Carnarvon, half a world away from the events. 15.5MB mp3 file, 43 minutes. (Transcript at Spacelog.) |

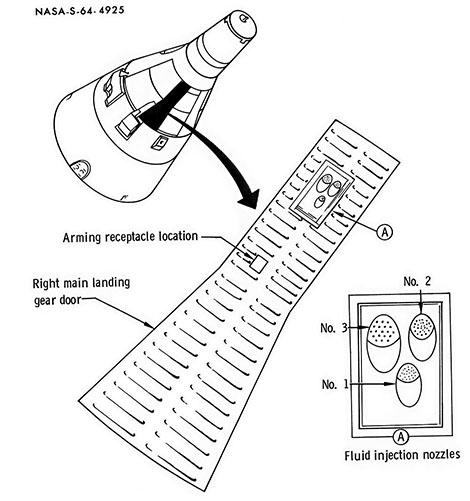

Here’s the background to the communications experiment, from NASA publication SP-4203, On the Shoulders of Titans, by Barton C. Hacker and James M. Grimwood, chapter 10. A reentry communications experiment had been proposed and accepted for Mercury-Atlas 10, but when the program ended with that mission unflown, it was suggested for Gemini. Tentatively assigned to Spacecraft 3 in March 1964, the experiment failed to win a firm place for months, largely because of its half million-dollar price tag. In July, however, the Office of Advanced Research and Technology in NASA Headquarters agreed to share the cost, and the experiment had its place in the mission confirmed. Research had shown that, for small objects, adding fluid to the ionized plasma during the reentry blackout could restore communications by lowering the plasma's frequency enough to allow UHF radio transmission to get through. Whether the same technique would work for an object as large as the Gemini spacecraft was now to be tested. A water expulsion system would be installed on the inside surface of one of the landing- gear doors, relics of the days when landing skids were to be used with its paraglider wing. The experiment was fully self-contained except for a starting switch inside the cabin to be thrown by the copilot when the spacecraft had fallen to about 90,000 meters. At that point, the plasma sheath would surround the spacecraft, blacking out communications. Water would be automatically injected into the plasma in timed pulses for the next two and a half minutes, while ground stations monitored and recorded UHF radio reception. |

| Audio recorded at Carnarvon and preserved by Hamish Lindsay. Digitised and edited by Colin Mackellar. |

Splashdown.

Just before hitting the water, Grissom threw a landing attitude switch, and Molly Brown snapped into the right angle to land, pitching both men into the windows and breaking Grissom's faceplate. They dropped into the Atlantic, 111 kilometres from the carrier USS Intrepid. The Gemini spacecraft produced less lift than predicted, so landed about 84 kilometres short of the target.

Splashdown was at 1416:31 local USEST Tuesday 23 March 1965 (0516:31 AEST 24 March).

After they landed the spacecraft was dragged along nose under water by a wind in the the parachute. All Grissom could see through the window was seawater flowing past, and with his Mercury fright still fresh in his mind, he released the parachute. This time he was not going to “crack the hatch” until the swimmers had attached the flotation collar, so the two astronauts suffered a miserable 30 minutes sealed in a “can” that was getting hotter by the minute, and being tossed around by the seas. “That was no boat,” complained Young with feeling.

GT-3 Recovery. NASA photo. |

Summary.

Young: "It was a really good test mission. Gus performed more than 12 different experiments in the three orbits he did a really great job I don't think he really got enough credit for the great job he did. He proved that the vehicle would do all the things needed to stay up there for fourteen days. We changed the orbit manually, the plane of the orbit, the first lifting reentry and we used the first computer in space." John Young's home town of Orlando, Florida, showed their support for him by presenting him with a 18 metre long telegram signed by 2,400 residents.

THE MANNED SPACECRAFT CENTER AT HOUSTON, TEXAS, COMES ON LINE.

Gemini III was the last time that the Mission Control Center at Cape Canaveral was used. The familiar flight controllers’ voices on the network saying, “This is the Cape” was replaced by “This is Houston” as the new Manned Spacecraft Center at Houston, Texas, came on line for the Gemini IV mission.

Chris Kraft had to add two more Flight Directors and flight teams to cover the long Gemini missions.

Personal Interviews:

Pilot John Young

Capcom Pete Conrad.

References:

Tracking Apollo to the Moon by Hamish Lindsay.

Carnarvon and Apollo by Paul Dench and Alison Gregg.

Failure is not an Option by Gene Kranz.

On the Shoulders of Titans: A history of Project Gemini by Barton Hacker & James Grimwood. NASA SP-4203.

NASA websites.

Audio edited and selected by Colin Mackellar.