Paul Dench

1934 – 2020

Carnarvon

Two tributes to Paul Dench – by David Johns (CRO 1970 – 74) and Alan Gilham (CRO 1965 – 67).

PAUL DENCH 1934 – 2020.

A quiet man, but a man of achievement, Paul Dench, passed away peacefully at Juniper Annesley on 26 June 2020. He was 86 years old.

He is survived by Joan, his wife of 64 years, and his children, Alan, Alison, Phil, Jo and David, and their children.

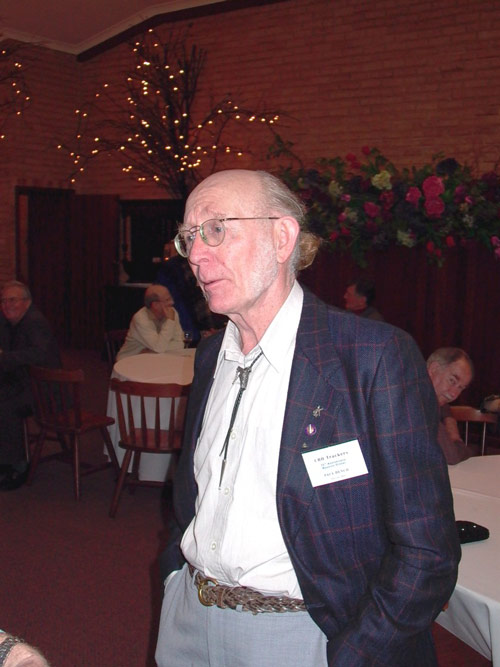

Paul Dench at the Carnarvon reunion in Perth in July 2004 for the 35th anniversary of Apollo 11. Photo by Terry Newman. |

From a modest upbringing in England, Paul went on to manage NASA’s (National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s) then biggest space tracking station outside of mainland America. He had a tremendous impact on many people through his varied careers and life, most of all his family. He will be sadly missed.

Paul lost his father in World War II but his mother raised him with love and encouragement and gave him the good principles which stood him well for the rest of his life. His first work was as a scientific assistant in the British Meteorological Office where he gained a ticket as a meteorological observer. He then worked with an array of meteorological instruments at several RAF sites on tasks as varied as climbing 350-foot-high towers to attach weather sensors and studying precipitation in clouds by flying in aeroplanes through turbulent thunder storms.

It was at that stage of his life that he met Joan and decided that he did not want to keep moving locations. He could see met devices becoming more electronically sophisticated so he transferred to the guided weapons branch at Farnborough and undertook telemetry engineering courses and worked on the Blue Streak Missile Program.

Paul and Joan married at Petworth, Sussex, England in August 1956.

Paul was troubled by the idea of working on a weapon of war and he was noticing that promotions came slowly in the civil service if you had not attended the right school so he began looking for opportunities in the private sector. For a while he worked for a company as a telemetry engineer and always remembered the day in 1957 when the factory at which he worked picked up the beep, beep, beeps of Sputnik. Paul says he just stood there, captivated and entranced, not then aware that he would later play a role in equally significant events.

About that time, he received an offer of employment in Sydney by AWA (Australian Wireless Australasia). Paul and Joan travelled to Sydney on the P&O ship Canberra but, while in transit, Paul was advised that AWA wanted him to work at Carnarvon West Australia (900 km north of Perth) on the yet to be built NASA Space Tracking Station. Paul and Joan were unsure about going to Carnarvon but Paul could see many challenges in the job so true to their adventurous nature, they decided to give it a go.

They settled temporarily in Sydney and Paul was dispatched to USA for a month of intense training which left Joan to cope in a new country with two toddlers, (Alan, 5 and Alison, 3).

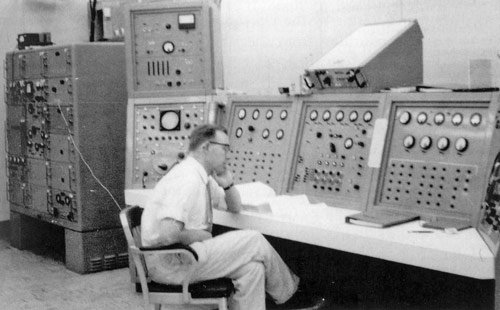

Paul Dench training for the new PCM telemetry equipment in Sarasota, Florida, 1963. From the book “Carnarvon and Apollo”, by Paul Dench and Alison Gregg. Page 51. |

The Dench family arrived in Carnarvon in mid 1963 and while Joan settled the family into a new and strange environment Paul threw himself into his new work.

Paul’s official position was “Telemetry Engineer”, a formal title indeed, but like all the new staff at Carnarvon, his tasks involved any mental or physical work that was necessary to change a sandy grassy ridge into a functioning tracking station.

In the simplest of terms, the role of the station was to receive telemetry data from NASA in the US and transmit that data up to orbiting spacecraft while ever the spacecraft were in line of sight from Carnarvon and similarly to receive downlink data from the spacecraft and relay that data back to America.

As the station took shape its first major task was to support the manned Gemini missions. NASA would send personnel who were familiar with astronaut tasks to Carnarvon to act as voice communicators between Carnarvon and the manned Gemini spacecraft. Usually the communicators were fellow astronauts and they would stay for about a week and be invited into all of the social activities of the town. Of the twelve Americans who later walked on the moon, three of them, astronauts Pete Conrad, Alan Shepard, and David Scott, had visited Carnarvon tracking station and worked closely with Paul.

Friday 25th November 1966, Joan and Paul Dench are in the row behind Laura & Les Brightwell who are being interviewed during Down Under Comes Up Live. Photo by Alan Gilham, scan by Colin Mackellar. |

Paul was a problem solver, he liked venturing outside his trained discipline and unscrambling other technical issues. When one of the new lunar tracking aerials was ready for trials, its direction controlling computers were months late in arriving. Paul managed a project with his team where they devised a model to give them pointing data for the new aerial so they could continue shakedown trials. When the new computers arrived, they confirmed the high accuracy of the procedure that Paul had developed.

When NASA commenced its Apollo program, sending men to the moon, the spacecraft would enter earth orbit and if all was well Carnarvon transmitted the ‘Trans Lunar Injection’ command that sent the space craft on a course to the moon. Also, Carnarvon’s geographic position allowed it the longest period of line of sight during the few hours prior to the return to earth of an Apollo spacecraft and thus Carnarvon’s reliable transmission of trajectory coordinates was a critical matter. Paul had a supervisory role when these Apollo command tasks were performed.

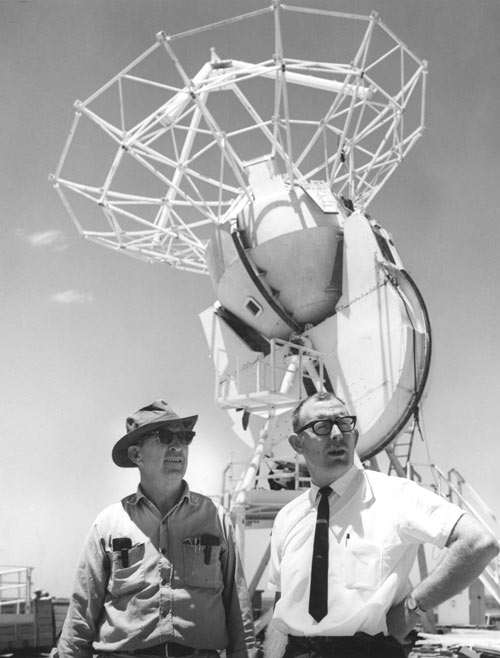

Collins Radio’s Sam Miller and Carnarvon Tracking Station’s Paul Dench stand in front of the 30 foot (9 metre) USB antenna under construction at Carnarvon. Photo by Hamish Lindsay, scan by Colin Mackellar. |

When reminiscing about his years at Carnarvon, Paul would comment that there was much hard work but there were many rewards. He said that some of the unforgettable moments for him were the first time he was responsible for the receipt of downlinked biomedical data from a real breathing human in space, of watching the first lunar lander probe wake up from a freezing fourteen day lunar night* and begin transmitting the first close up views of the moon’s surface, pixel by pixel, and of course the big one, receiving the voice and seeing a speckly TV image of Neil Armstrong on the moon.

There were also worrying times too like when Carnarvon was receiving down linked data from the crippled Apollo 13 spacecraft and everyone on the station could see the evidence that three fellow humans were up there running out of oxygen and battery power and they might die in space. Carnarvon played a critical role during the return of Apollo 13 and Paul spoke of the feeling of utter relief that he and everyone on the station felt when the astronauts returned safely to earth.

Paul always spoke with pride about the achievements of the Carnarvon tracking station and he attributed it to the quality of the staff that he worked with and typically he always understated the significance of his own contribution. His capacity to solve a wide array of technical and management issues did not go unnoticed by AWA and, in 1968, he was appointed Chief Engineer of the tracking station. In 1970 he was appointed Company Manager of the whole site.

But Paul was more than just an engineer and a manager. He took an active interest in social issues in Carnarvon. He was passionate about the need for a high school in the town and he was instrumental in getting the Government to build one. He was invited to become a Justice of the Peace (which amused and flattered him because of his English working-class background) and, on many occasions, he functioned as an acting magistrate, deliberating on minor offences in the town. He and his family were active in many of the town’s clubs and he was encouraging to other tracking station staff who participated in town activities.

As new satellite to satellite communications developed, NASA began to close many of its ground-based tracking stations. Carnarvon was in a better geographic position for a tracking station than Australia’s east coast tracking stations and Paul argued vigorously that Carnarvon should not close but politics and accountants overruled him. The Carnarvon tracking Station, then with a staff of about 200 people, closed in 1975 with most of its tracking functions being transferred to Australia’s east coast tracking stations

It then fell to Paul, now the manager, and who had done so much to physically and technically build the station and its work teams, to dismantle those very work teams and terminate the services of the many good men and women who had given their all to the station. This involved many difficult decisions that affected people’s lives and families and Paul spared no effort to do that job with fairness, honesty, and openness.

Paul, who had been one of the first people to work at the station, was also one of the last to leave.

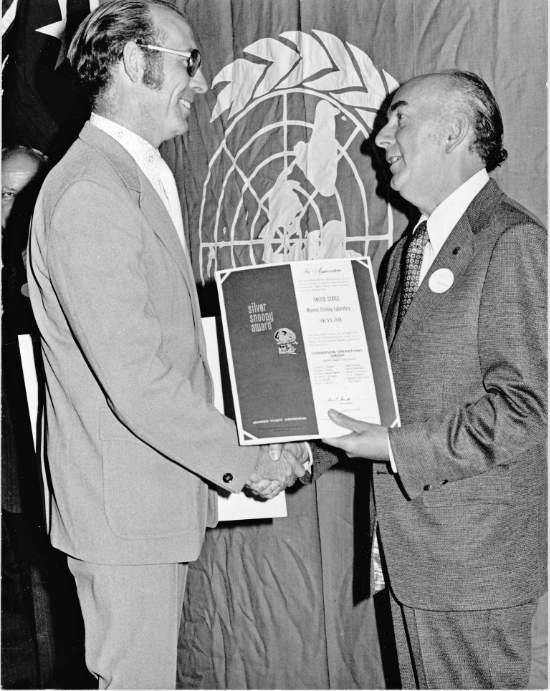

Paul Dench receives the Silver Snoopy from Tecwyn Roberts (Director of Networks at Goddard Space Flight Center) at the Carnarvon closing ceremony, 06 November 1974. Photo courtesy of Paul Dench. |

Paul’s baby, the Carnarvon Tracking station, is now just a memory. Where Paul and others had once worked long hours to make the missions successful, now only the concrete bases of the buildings can be seen.

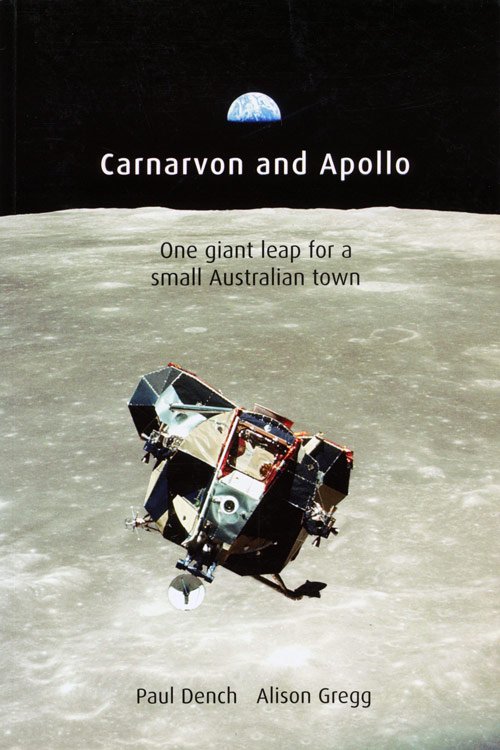

But all is not forgotten. Paul and Alison Greg wrote a book “Carnarvon and Apollo, One giant leap for a small Australian town” which describes some of the technical work of the station and how the tracking station staff blended into the town. The Carnarvon Shire Council supported the book and it was published in 2010.

Carnarvon and Apollo, by Paul Dench and Alison Gregg. ISBN 9781877058974. |

Also, in 2012, a Perth based businessman and the people of Carnarvon opened a space museum at Carnarvon. Paul was generous with his time in supporting the museum and gave books and many personal items for the displays.

When the Tracking Station closed in 1975, Paul and his family moved to Perth. Paul embarked on another very successful career. After obtaining a Graduate Diploma in Education at WAIT (now Curtin University) he taught in Government schools, was a tutor supervisor at Murdoch University and then a project leader in the Department of Education, focussing on the use of computers in schools.

But Paul’s skills as an engineer were not forgotten and, a year after he had left Carnarvon, AWA offered him the Chief Engineer position at the then expanding Tidbinbilla Deep Space Tracking Station near Canberra. It was a prestigious offer, and Paul was sorely tempted, but by then his work had gone off in a different direction and he declined, though he later said he often thought of what might have been if he had accepted.

The Educational Computing Association (E.C.A.W.A.) elected Paul to be its first Computer Educator of the Year in 1995 – and then a Life Member in 1998. Before retiring in 1997, Paul was employed at Scotch College for six years to teach computing and to ‘embed computer use throughout the whole school’.

Paul’s civic contributions continued after he left Carnarvon, including being a Kings Park guide for ten years and completing 40 years of service as a JP.

Paul will be long remembered for his exceptional problem-solving skills, his fairness as a manager, his civic contributions, and his basic decency as a fellow human.

David Johns, CRO 1970 – 74.

3rd July 2020.

* Paul happened to be visiting Tidbinbilla in July 1966 when Surveyor I was awakened by the team after surviving a lunar night.

Muchea’s Jack Duperouzel with Carnarvon’s Paul Dench at an Australia Post space stamps launch event at Perth Observatory, 2nd October 2007. |

A tribute to Paul Dench

I first met Paul in Dallas when we were on the first Unified S Band course run by Collins Radio.

To meet your boss in such circumstances was a strange occurrence. I was pleasantly surprised by his welcoming attitude and his obvious wish that all would go well and he ensured that we had good accommodation and looked after our welfare whilst we were in Dallas.

Working with Paul at the Carnarvon Tracking Station furthered my respect for him as an Engineer and a work mate. He looked after his personnel and respected their opinions.

Paul and his wife (Joan) visited us in the UK in 2004 and we spent some time discussing the events leading up to the installation and commissioning of the USB system which I hoped helped him in writing his book with Alison Gregg.

My condolences go out to Joan and her family.

Alan Gilham, CRO 1965 – 67.

4th July 2020.

Also see –

In 1994, Paul and Joan Dench recorded their memories of Carnarvon – each on an audio cassette tape. The tapes were digitised in 2019 and are available on this page in our Interviews section. Both recordings are wonderful reminiscenses of a tracking station, a town and a community. |