Philip Clark

1941 – 2023

Orroral Valley

Philip and the Orroral Valley 26 metre antenna. Image adapted from Philip’s book Acquisition! |

Philip Clark began his space tracking career at Orroral Valley at the end of 1966 as a technician. When the station closed in 1985 he was the Senior Operations Supervisor.

After leaving Orroral he was engaged in other senior technical, engineering and research positions both in government and private industry.

In 1993 Philip was awarded a National Medal of Australia for Service. In 1999, he was awarded a Master of Science degree from the University of New South Wales at the Australian Defence Force Academy.

Through his interest in amateur radio he is one of the few people to speak with both Russian cosmonauts on the USSR’s Mir space station – and American astronauts on the Space Shuttle – from his car!

Philip authored a number of technical manuals and articles for technical magazines.

On the website for his book The Final Orbit, Philip shared a little of his story.

He wrote:

“I have always had an interest in things electronic and technical from a quite early age. By the time I was about 7 or 8 I was building make-believe spaceships under the bed and starting to use electronics. I said to my parents “One day I am going to fly a spaceship”. In later life, only about 20 years later, I actually did this by remote control! (I made another prediction as a young boy, that I would fly an aeroplane. In later life, not only did I fly one, but I owned it as well!)

I read books about space adventures and travel such as ‘Stand by For Mars’, ‘Laurie’s Space Annual’ ‘By Spaceship To The Moon’, ‘The Adventures Of Captain “Space” Kingsley’ and ‘Mariners of Space’ before I was about 10 years old.

I was still quite young when I found out that amateur radio was a more specialist side to electronics. I suspect my interest in it may have been partly due to one of my teachers, at Largs Bay Primary School. I think it was my grade seven teacher at the time.

However, it was not too long before my interest in things electronic started to grow further. Before I was 11 years old I was already building electronic equipment. At age 12 I had been given a junior ‘teach yourself’ book called ‘Radio for Boys’. Before I reached the age of 13 years I was building radios from this book.

In the early 1950s germanium semiconductor diodes became available. These could be used in crystal radio receivers without the tiresome fiddling with a ‘cat’s whisker’. In 1954 while I was in grade seven at primary school I managed to buy one of these devices. It cost the princely sum of nine shillings and six pence. This was a lot of money for a boy who was only getting two and six per week pocket money. After some experimenting with this device I eventually managed to construct a crystal set in a match box. Most of the parts were in the sliding tray of the box. The tray that had a coil of wire around it. There was another coil of wire on the outside of the box. This arrangement meant that the radio could be tuned by sliding the tray in or out.

When I had successfully made this, I took it to school and offered it for sale at the enormous price of 19 shillings and six pence, just six pence less than one pound. This price was well outside of the finances of most students but as I recall I did sell two of them during the year. Some time later I was able to purchase my first transistor. These first transistors could only be used for quite simple applications and were exceedingly easy to damage or destroy if wrongly used. Because of the cost I had to be very careful experimenting with them.

When I went to secondary school I managed to put my electronic knowledge to good use. Even before I was in second year I had somehow arranged for myself to take over the setting up of the sound system for school assemblies and most other functions. Before the assembly I would get the amplifier, microphone and all of the necessary connecting cables and accessories from the store room and set up the system. I would test it and make sure that everything was ready and working for the assembly. I became very proficient at this. In my intermediate year, the third year, of secondary school in 1957, I was presented with a prize for services to the school for my skill and ability in setting up the amplifier at the school assemblies. At the time of the presentation it was said that the amplifier system had never worked so well as when I was setting it up. I was very pleased about this. The prize that I was awarded was a book called ‘The Boy Electrician’. I still have this book.

After leaving secondary school I joined the Commonwealth Government Post Master General’s Department (The forerunner of Telstra) and trained as a radio communications technician. After successfully passing the examinations to qualify as a Senior Technician I later left the PMG and became the Foreman of the Adelaide mobile radio section of Telecommunications Company of Australia (TCA).

It was during this time I saw an advertisement for technicians to work at a new space tracking station being established in the Australia Capital Territory. I applied for a position and was accepted. I moved to Queanbeyan (near the ACT) in 1966 and commenced work at Orroral Valley Spacetracking Station. It was an amazing place! The equipment and technology was well ahead of anything I had previously seen.

Philip is on the right in this photo taken in January 1967. NASA’s Dr George Mueller is addressing members of the Orroral Valley team in the station’s canteen. Dr Mueller was in Australia as part of a Network Inspection Tour which included visits to Honeysuckle Creek and Tidbinbilla. |

In late 1981, the crew of the first Space Shuttle orbital flight, STS-1, visit Orroral Valley to thank the staff for their support. Here STS-1 Astronauts Bob Crippen and John Young sign mementos for the station staff. Watching them is Philip Clark. Dick Simons and Peter Uzzell look on at right. Photo: Philip Clark. |

I remained at Orroral tracking station until it closed in 1985. In hindsight, it was absolutely the best job I ever had! I advanced through all grades of technician into supervisory positions, eventually becoming the Senior Operations Supervisor in charge of all the actual operational tracking shifts. At one time during this period I was the senior technician in Australia for all voice communications to the Space Shuttle.

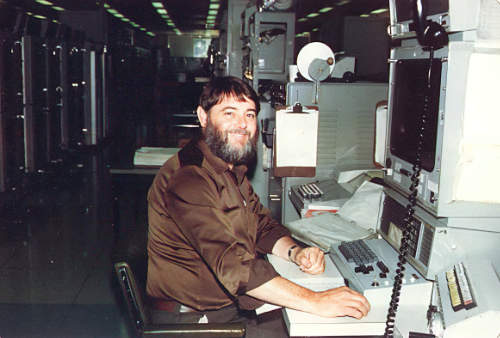

Philip at the DDPS (Digital Data Processing System) console at Orroral Valley in November 1984. Photo: Philip Clark and Rob Quick. |

After Orroral tracking station closed I formed my own company designing and manufacturing specialist electronic equipment for the security industry in Canberra. I was headhunted away from this to join an electronic security company as their Technical Manager. I later left this company to become a senior technician in the computer science department of the Australian Defence Force Academy. While here I undertook studies to gain a Master of Science degree.

I later joined the commonwealth Defence Science and Technology Organisation as research scientist working on classified military communication systems until my retirement in 2005.”

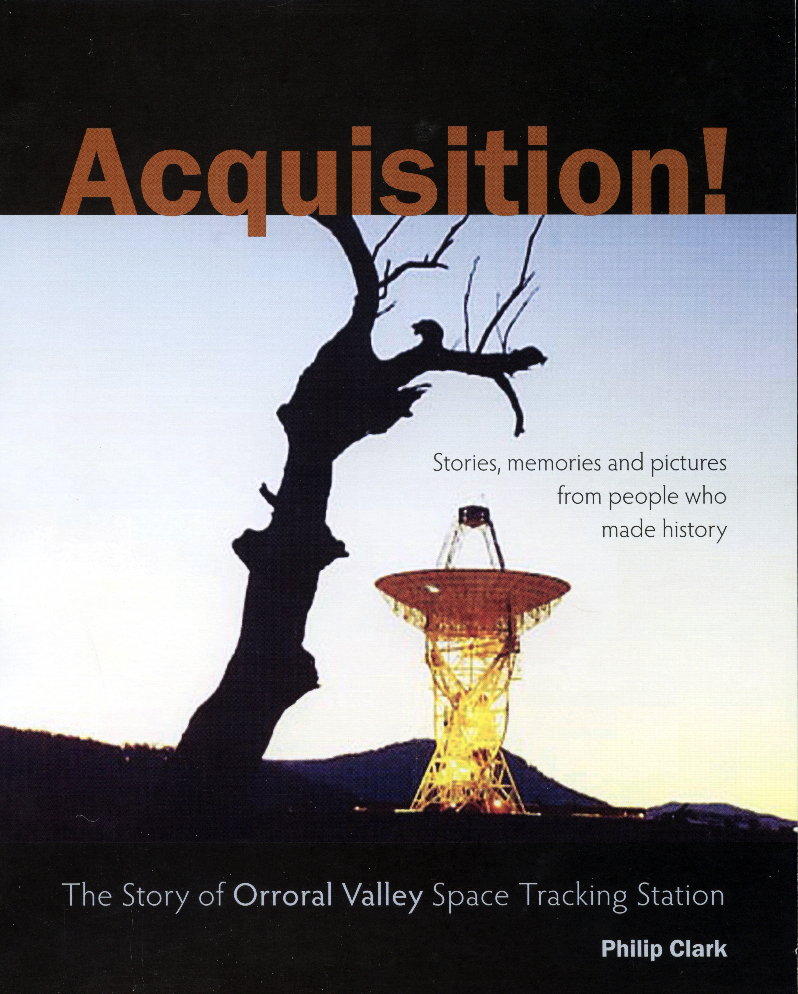

In 2012, Philip published the definitive book about Orroral Valley Tracking Station. Entitled, Acquisition!, it details the history of the station and contains many photos of the men and women who made Orroral Valley a great place to work.

In 2019 he published The Final Orbit, with a focus on Orroral Valley’s support of the early Space Shuttle flights. (Philip kindly shared his audio recordings of STS-1 passes on this page.)

Acquisition: The Story of Orroral Valley Space Tracking Station, by Philip Clark, 2012. ISBN 9780987256607 |

Inset: Philip Clark at Orroral Valley, 1983 – and his book The Final Orbit. ISBN 9780987256638 |

In 2002, Philip and his Orroral Valley colleague Rob Quick, produced a CD of photos taken during the life of the tracking station. With thanks to Philip and Rob, we’ll be featuring a number of those on the website.

In loving memory of Philip Clark, 1941 – 2023.