1923 – 1995

Bob Leslie was the first Station Director

of Tidbinbilla – and later Assistant Secretary, American Projects Branch.

|

|

|

At the opening ceremony for Tidbinbilla.

Australian Minister for Supply, Mr (later Sir) Allen

Fairhall (left); Australian Prime Minister, Sir Robert Menzies

(centre) with Station Director Bob Leslie (right).

19th March 1965.

Photo kept by Clive Jones, passed on by John Heath,

scanned by Mike Dinn.

|

|

|

|

On a sunny summer day, 7 February 1969, Ozro M. Covington and

Dale W. Call from the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland paid Honeysuckle

Creek a visit.

From left: Willson Hunter (NASA Senior Science Rep in Canberra),

Tom Reid (Station Director), Ozro Covington, Dale Call,

and Bob Leslie (previously Station Director at Tidbinbilla).

Photo: Hamish Lindsay.

|

Bob Leslie was frequently called on to provide

expert commentary for the electronic media. He was a commentator on ABC-TV (Australia) for the launch of Apollo 11, as well as on ABC Radio for the Apollo 11 lunar landing.

|

Listen to

a 38 second (160kb) mp3 recording

– from ABC Radio at about 7:30am Australian Eastern Time, on Monday

21st July 1969. Bob discusses the timing of the start of the Apollo

11 EVA – and the likelihood that Australian tracking stations would

provide the TV coverage. (with thanks to Dwight Steven-Boniecki.) |

See also this extract from “Uplink-Downlink” by Doug Mudgway

The Need for a Second Network

“To support the more sophisticated missions

of the 1965 to 1968 period, the DSN recognized the need to expand and improve

its communications, mission, and network control capabilities. The two major

lunar missions nearing launch readiness, Lunar Orbiter and Surveyor, would

pave the way for the start of the Apollo program and would transmit data streams

at thousands of data bits per second rather than the tens or hundreds of bits

per second received from the Mariners and Rangers. The increased complexity

of the spacecraft would require expanded and faster monitor, control, and

display facilities.

For the first time, the DSN began to find

that the simultaneous presence of several spacecraft on missions to different

destinations created new problems in network and mission control. The vexing

problem of DSN “antenna scheduling” began to arise as several spacecraft

began to demand tracking coverage from the single DSN antenna available at

each longitude. The difficulty of assigning priority among competing spacecraft

whose view periods overlapped at a particular antenna site was to prove intractable

for many years. The problem was exacerbated by competition between flight

projects from NASA Centers other than JPL, each of which felt entitled to

equal consideration, for the limited DSN resources. The DSN was placed in

the impossible situation of arbitrating the claims for priority consideration.

The regular “Network Scheduling” meetings conducted by the DSN often

resulted in the establishment of priorities that were determined more by the

dominant personalities in the group than by the real needs of the projects.

With all of these imminent new requirements

in mind, NASA decided to embark on a program to construct a second network

of DSN stations. Arguments as to where the stations were to be located were

complicated not only by technical considerations, but by political and international

considerations. There were already two stations at Goldstone, one at the Pioneer

site and a second at the Echo site. Eventually, NASA decided to build two

new stations, one at Robledo, about 65 kilometers west of Madrid, Spain, and

the other at Tidbinbilla, about 16 kilometers from Canberra, Australia.

NASA looked to the Spanish Navy’s Bureau

of Yards and Docks to design and construct the Robledo station. For its new

facilities in Australia, NASA dealt with the Australian Government Department

of Supply through its representative, Robert A. Leslie.

As an Australian foreign national, Robert

A. Leslie played a major role in shaping the relationship between NASA-JPL

and the Australian government, on whose good offices NASA depended for support

of its several tracking stations in that country. With family origins in the

state of Victoria, Australia, and an honors degree in electrical engineering

from the University of Melbourne (1947), Leslie had worked on radio controlled

pilotless aircraft for the military in both England and Australia for fifteen

years before he encountered NASA. He was a high-ranking officer with the Australian

Public (Civil) Service (an affiliation that he retained throughout his career)

when, in 1963, he became the Australian government’s representative for

NASA’s new deep space tracking facility being built at Tidbinbilla, near

Canberra in southeastern Australia.

|

Inaugural Station Director Bob Leslie (centre) chats with an unidentified group (a note on the back of the print indicates they are Station Directors) over a BBQ lunch in this WRE photo taken on 20th August 1963.

It was apparently taken at the Tidbinbilla Nature Reserve.

Photo from the Tidbinbilla Archives. WRE ID MF63-23-26.

Updated 2024 scan: Colin Mackellar. |

As might be expected, the success of a NASA

venture in a foreign country depended to a large extent on the personalities

of the people who were directly involved on each side of the international

interface. The foundation for the success of what later became the Canberra

Deep Space Communications Complex (CDSCC) was, in no small part, due to Bob

Leslie’s personal ability to “get along” with people at all

levels. In representing the Australian side of negotiations between NASA and

JPL, Bob Leslie was firm but gracious, capable, and friendly. His unassuming

“paternal” manner endeared him alike to counterparts at NASA, his

colleagues at JPL, and his staff in Australia.

Along with a few key Australian technical

staff members, Leslie spent a year at Goldstone assembling and testing the

electronic equipment that would subsequently be reassembled at Tidbinbilla

to complete the first 26-meter tracking station (DSS 42) at the new site.

He was the first director of the new Complex when it began service in the

Network in 1965. It was there that he established the procedures and protocols

on which all future DSN operational interactions between JPL and the Australian

stations would be based.

A few years later, in 1969, Leslie left the

“hands-on” environment of the deep space tracking station to head the Australian Space Office, a branch of the Australian Government

that, under various names and government administrations, would guide future

expansion and consolidation of all NASA facilities in Australia. In that capacity,

his charm, experience, and wisdom served the DSN well.

|

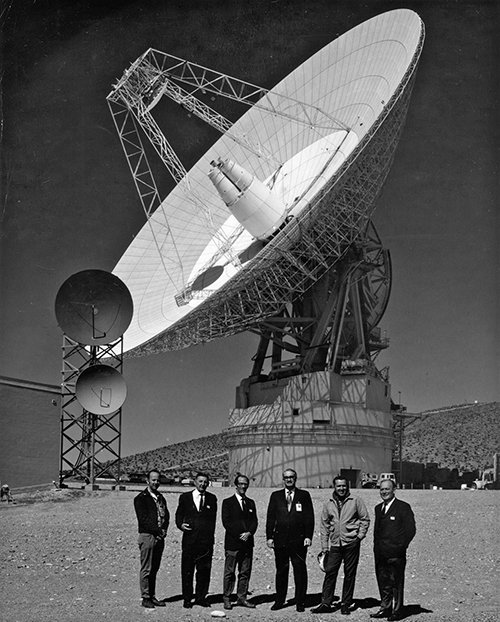

Bob Leslie, at right, in front of the 64 metre DSS-14 at Goldstone.

From left: 1. unidentified, 2. unidentified, 3. Alan Sinclair (Aust. Dept. of Supply), 4. Dick Fahnestock (Canberra JPL Rep), 5. Tom Potter (JPL Station Director), 6. Bob Leslie (first Tidbinbilla Station Director).

Photo preserved and scanned by Michelle Sinclair. |

Leslie’s build was stocky and solid,

his appearance craggy, his attitude “laid back.” Cheerful, sociable,

easy to talk to, and blessed with a good sense of humor, he was held in high

regard by everyone he met, Australian or American. Tennis was his sport, fishing

his hobby, and “do-it-yourself” home building his passion. In his

younger days, he actually excavated the ground with shovel and wheelbarrow

and single-handedly built the family swimming pool at his home in Canberra.

Many a JPL engineer enjoyed a poolside barbecue at the Leslie home in the

course of a technical visit to the station.

Robert Leslie retired in 1983 and died in

Canberra, Australia, in 1996. [Actually, 1995.]

By mid-1965, the two new stations were completed

and declared operational. The DSN then had two stations in Australia, (Woomera

and Tidbinbilla), one in Spain, and one in South Africa. In addition, a permanent

spacecraft monitoring station had been built at Cape Canaveral to replace

the temporary facility with its hand-steered tracking antenna. Impressive

as this growth was, still greater changes were in progress.”

Reproduced

from pages 64–66 of the book Uplink–Downlink: A History

of the Deep Space Network 1957-1997 (Washington, D.C.: NASA SP-2001-4227,

2002), by Douglas J. Mudgway. Reproduced

from pages 64–66 of the book Uplink–Downlink: A History

of the Deep Space Network 1957-1997 (Washington, D.C.: NASA SP-2001-4227,

2002), by Douglas J. Mudgway.

With grateful thanks to Doug Mudgway

for his permission to use this material.

A scanned version of the entire book is available at Google Books.

See also Doug Mudgway’s book, “Big

Dish: Building America's Deep Space Connection To The Planets”. |