Walt Larkin – official portrait, Canberra, circa 1970.

Walter Larkin – First Goldstone Complex Director

“Mr. Goldstone”

1923 – 2007

Walt Larkin – official portrait, Canberra, circa 1970. Photo courtesy Maureen Hay. Scan: Colin Mackellar. |

Walter Larkin was born in San Francisco at the end of December 1923 and went on to become a key participant in mankind’s first exploratory steps into space.

Along the way, he came to love Australia and consider it a second home.

At the age of five, Walt’s parents separated and he went to live with his grandparents who ran a “chicken ranch” in Sonoma, California.

Within a year or so, however, he had returned to San Francisco and found accommodation in a series of boarding houses. These he considered wonderful places to grow up. Walt had to learn to be independent, including in his studies and in finding jobs to support himself at school. He sold newspapers, washed pots and pans at a local restaurant, and, when he reached high school, even operated the school’s elevator.

Walt would attend high school in the morning, then go to the trade school in the afternoon, learning to build and repair radio receivers. From 3:30pm, he had a job at a radio repair shop.

The Second World War came to America with the bombing of Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, just before Walt’s 18th birthday. Initially, Walt joined the Army Signal Corps as a civilian, building and testing radio equipment for tanks. In September 1942, he joined the Navy and trained as a Marine Technician, soon specialising in the new field of Radar.

After various assignments, Walt spent the rest of the war repairing aircraft electronics in the western Pacific.

In 1951, the Korean War mean that Walt was recalled to active service and posted to Memphis, Tennessee, where he instructed students in aircraft electronic and hydraulic systems. At the end of 1951 he returned to California to marry Patricia Jean Waldron, whom he had met through his cousin.

Fort Bliss and White Sands

After a spell teaching at the Naval Air Station in San Diego, Walt began looking for civilian work. Having gained employment as a Philco Field Engineer, he moved with Pat to El Paso, Texas where he taught radar surveillance to military personnel at Fort Bliss Army Base.

In 1955, now with twin daughters Maureen and Kathleen, Walt applied for a job with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Instrumentation section at the White Sands Proving Ground in New Mexico.

Son Blake was born at White Sands.

Walt was responsible for the control of the early guided missiles, including the Corporal, and the command radar.

This work concluded, the family moved to JPL at Pasadena where Walt helped develop a telemetry and guidance system for the US Army’s Jupiter intermediate range ballistic missile. After six months, he was part of the team which moved to Cape Canaveral to test the equipment.

The Cape

During this time, the IGY (International Geophysical Year, 1 July 1957 to 31 December 1958) began.

The US had planned to launch a satellite during the IGY as part of international co-operation into understanding the Earth’s environment, however the USSR surprised the world by launching Sputnik 1 on 4th October 1957.

This led to the acceleration of US efforts to launch a satellite and Walt was part of the team which successfully launched Explorer 1 on January 31 1958.

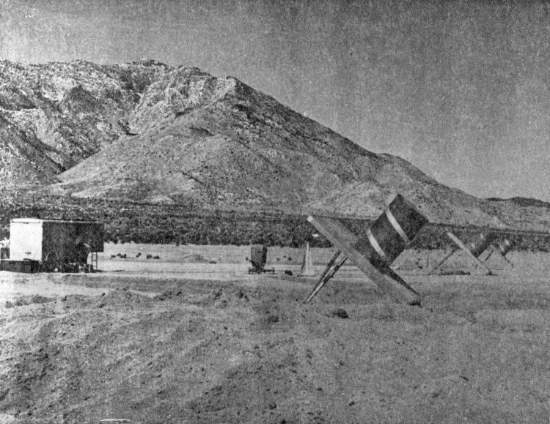

The rudimentary tracking network for Explorer 1 consisted of four Microlock antennas – two fixed installations at Earthquake Valley, California and Cape Canaveral, Florida, as well as portable stations at University College, Ibadan, Nigeria and at the University of Malaysia in Singapore. Communications with the Nigeria and Singapore stations was via coded commercial telegrams, often employing local runners to get messages to and from the telegram offices!

Launch of Explorer 1 onboard a Jupiter-C launch vehicle. NASA photo. |

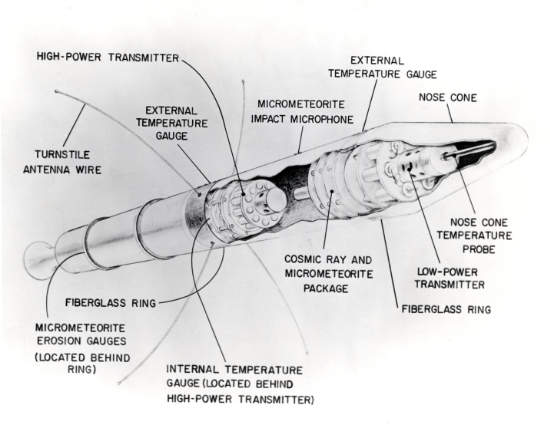

A JPL diagram of Explorer 1 – preserved by Walt Larkin. Text on the back of the photo reads: Californla Institute of Technology The scientiflc earth satelllte put Into orbit by the modifled Jupiter C launching vehlcle is 79 Inches long and weighs 29.87 pounds. The launching was made jointly by the California Institute of Technology Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the Army Ballistic Missile Agency. In the artist’s sketch, above, the instrumentation in the satellite is identifled. The Instrument-carrying section forward is attached to the final-stage rocket in the rear so that the two orbit as one unit. Fanning out from the mid section is the antenna, made up of whip-like rods with welghted balls on the ends of the rods. The rotational spin of the satellite forces the antenna out from the satellite. Both the high-power transmitter, which radiates 60 milliwatts of radiofrequency power, and the low-power transmitter, which radiates between 10 and 20 milliwatts of power, continuously transmit the information on elght channels to ground stations. (One milliwatt is one thousandth of a watt.) With thanks to Maureen Hay. Scan by Colin Mackellar. |

The Microlock station at Earthquake Valley, California. Image from A History of the DSN by William Corliss. NASA CR-151915, May 1, 1976. Scan: Colin Mackellar. |

The Microlock system had been developed by JPL as part of its missile testing for the US Army, but it was clear that for future space missions something more permanent was needed – and something which could track probes to considerable distances from Earth.

Goldstone

After the success of Explorer 1, the US Air Force established the Pioneer Program to send probes to the vicinity of the Moon. That work was soon transferred to the Department of Defense’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA).

To support Pioneer and later deep space programs, ARPA planned a global tracking network tentatively named World Net or TRACE (Tracking and Communication Extra-terrestrial), with a station in the USA, and two others – one on the island of Luzon in the Philippines, and the other in Nigeria. So, in 1958 ARPA ordered three 85-foot (26 metre) polar-mounted parabolic antennas from the Blaw-Knox Company. (At the time, the antennas, designed for radioastronomy, existed only on paper – none had yet been built.)

JPL would build and operate the antennas for ARPA.

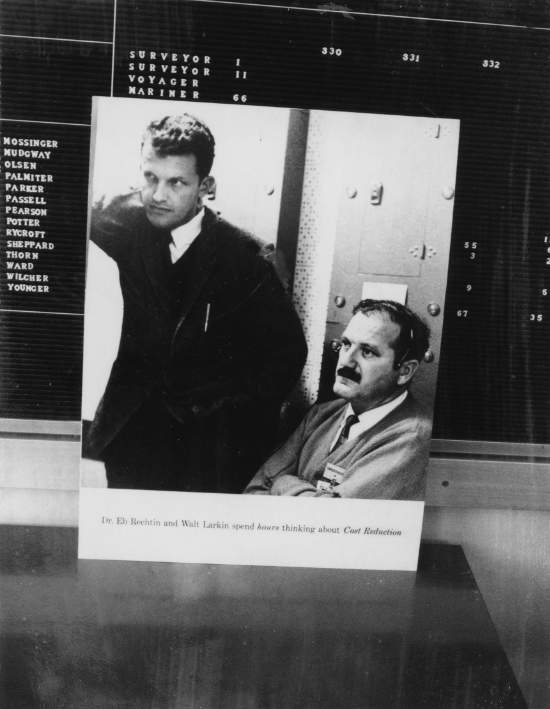

JPL’s Dr Eberhardt Rechtin (now known as ‘the Father of the DSN’) approached Walt Larkin to be Manager of the first station. It was to be located near the Goldstone Dry Lake on the US Army base at Camp Irwin (now Fort Irwin), 50 miles from Barstow in California’s Mojave Desert. The Larkin family moved to Barstow, and soon welcomed another daughter, Barbara.

This picture of Dr Rechtin and Walt Larkin was photographed at JPL. Polaroid courtesy Maureen Hay. Scan: Colin Mackellar. |

JPL only had about eight months from site selection to having the station operational. It was a very busy time!

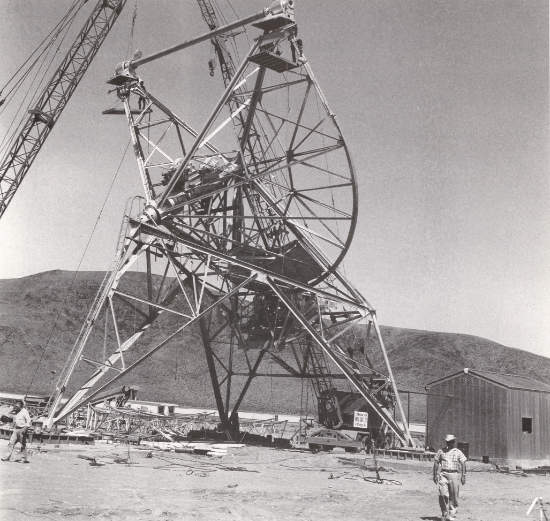

Part of the team building the first antenna (Pioneer) at Goldstone, 1958. Walt is in the centre at back. Photo courtesy Kathleen Larkin du Plessis. |

The Pioneer antenna at Goldstone at the same time. Photo from Picture Album of the Deep Space Network, internal JPL publication compiled by N A Renzetti and D Worthington, JPL, July 1, 1994. Courtesy Mike Dinn. Scan by Colin Mackellar. |

Walt wrote of the beginnings of DSIF 11, the first station of what would become the Deep Space Network,

“We were assigned 69 square miles of property, with not much on it but a few dirt roads, dry lakes, hills, sand and gravel. There was no water, no communications and no structures. I was given $25,000, to build a control building and $50,000 to build a generator plant.

Roads were bulldozed into the site, but the steelworkers who were erecting the antenna flew in from Barstow every day by private plane, touching down on a primitive landing strip.

Water was trucked in by a 5,000 gallon tanker and communication wire was laid on the ground to Camp Irwin; a distance of about 15 miles. The phones were of a military-type, housed in canvas bags. To call the Camp Irwin operator it was necessary to turn a ringer crank located on the side of the canvas bag. All the available space in the control building was for equipment. We rented some trailers from a movie production company to house the dormitory, offices, cook’s shack/cafeteria and construction office.

I got a lot of help by calling on the Army located at Camp Irwin. They helped us with transportation. We used leased cars to get from Barstow to the army transportation motor pool, and from there we would take off-road vehicles to the site.

This miner’s shack was the only building for miles of Goldstone Dry Lake.

Photo from Picture Album of the Deep Space Network.

One of the dry lakes out at Goldstone, aptly named Goldstone Dry Lake, was actually converted into an airport. It was dry most of the year, but in case it was underwater, we had a very straight road that went to the airport and the small planes used that road as a runway. In that case we swung barriers down over the road, so no cars could use it. If the planes were coming in at night we had our own generators and lights at the airport. On approach, the pilot would send a signal from the plane which would start the generators to light up the runway. This routine is still used to this day.We all shared some of the tough jobs. For instance, we had a few days of many flat tires as people were covering all of the 69 square miles, on and off road driving. We got everybody on site to walk along the main road behind a large, slow moving truck and manually remove any sharp stones or objects and toss them into the back of the truck. I mean everybody, including myself, engineers, technicians, supervisors, electricians and transport people. There was a lot of that type of spirit out there. People did jobs that weren’t really related to the work they were doing, but which needed to be done to complete the total job.” [Larkin, pp. 58-59]

On December 3rd 1958, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory was transferred to the newly created National Aeronautics and Space Administration which came into being on October 1st 1958. Consequently, the Goldstone site became part of NASA. ARPA did not have the opportunity to build its planned network – that job would fall to NASA. (And the two overseas antennas APRA planned for the Philippines and Nigeria eventually built in Australia and South Africa.)

The Pioneer antenna by night during construction. Photo from Picture Album of the Deep Space Network. |

The first assignment for Goldstone was to track Pioneer 3, launched to fly by the Moon on December 6, 1958. Only reaching an altitude of 63,500 miles, it fell back to Earth somewhere in central Africa. Goldstone tracked the probe 10 hours of the 24 hour flight.

The first successful launch supported by Goldstone was Pioneer 4 on March 3 1959. Departing from Cape Canaveral, it became the first US probe to escape the Earth’s gravitational field, as it flew past the Moon and into a solar orbit. Goldstone tracked the probe out to 435,000 miles, at which point the spacecraft’s batteries were depleted.

As a result of tracking Pioneers 3 and 4, this first Goldstone antenna, later officially named DSIF 11, came to be known as the Pioneer station.

It was during this busy time in Barstow that Walt and Pat’s son Brian was born. Also during these years, Walt’s eldest son, Craig, would come to spend time with the rest of the family during holidays.

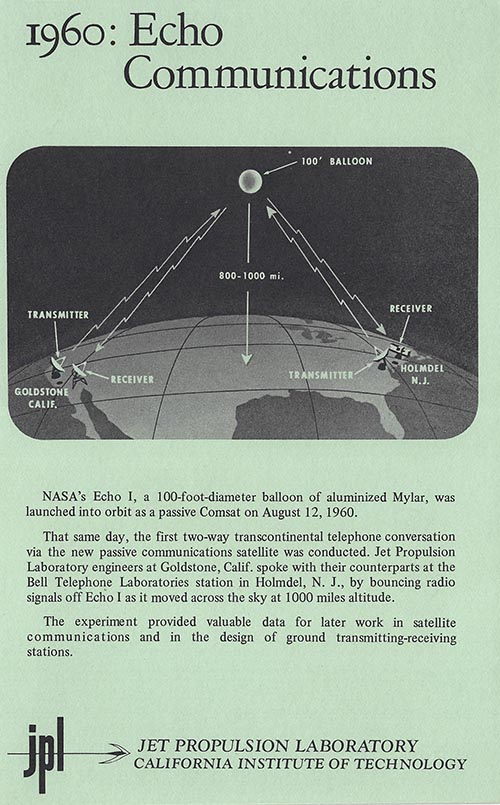

There were many ‘firsts’ at Goldstone – including the ‘Echo Balloon’ tests, bouncing a signal between the new ‘Echo’ antenna at Goldstone and Bell Labs’ horn antenna in Holmdel, New Jersey, via Echo 1, a 100-foot-wide inflatable satellite.

The Echo Balloon experiment. Les Whaley (Tidbinbilla) preserved this snippet from a JPL publication. Scan by Colin Mackellar. |

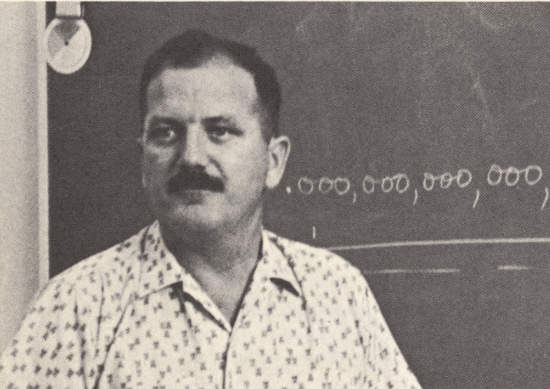

Walt Larkin at Goldstone in a Bell Labs film about the Echo Balloon experiment, entitled “The Big Bounce”. Screen capture and image processing by Colin Mackellar. |

Walt Larkin as featured on page 36 of the Fall 1963 issue of Trajectory, Volume 3, Number 1, published by Lockheed Missiles and Space Company. With thanks to Maureen Hay. |

The Echo site in 1965. Photo by Pat Delgado, Island Lagoon. Scan by Jan Delgado. |

The most ambitious program for Goldstone in the early days was Ranger. The Ranger probes were intended to crash into the Moon, returning high resolution television pictures of the surface as they approached. With launches starting in August 1961, the first six spacecraft were plagued by various technical problems and were unsuccessful. It wasn’t until July 1964 that Ranger 7 succeeded in returning more than 4,000 images as it plunged in to the Moon near the crater Copernicus.

Then came the Surveyor lunar soft landers, and the Mariner probes to Venus and Mars, and more.

By this time, the Deep Space Network had become a reality. The first two 26 meter stations outside the US – DSIF-41, Island Lagoon, Woomera, and DSIF-51, Johannesburg, had been built in 1960 and 1961. Walt visited Woomera on a number of occasions during the building of Island Lagoon and the later upgrade of the station from L-Band to S-Band.

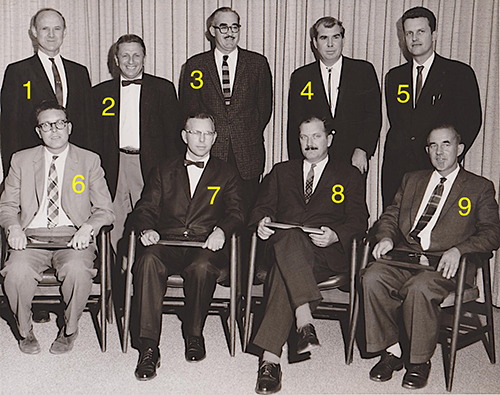

Presentation of plaques at JPL for the support of Mariner 2, 1963. 1. William Pickering, JPL Director. Scan: Bill Mettyear Jr. Thanks to Chuck Koscielski, Mike Dinn and Richard Mallis for help with identification. |

As well, Goldstone had grown considerably, and the Pioneer station was chosen to house the ‘Wing’ for the new Goldstone Apollo station which was being built nearby.

The Pioneer antenna, DSIF-11, in 1965, after S-Band capabilities were added. Photo by Pat Delgado, Island Lagoon. Scan by Jan Delgado. |

In the control room of the Echo station during public tour of Goldstone in April 1963. Howard Olsen, Goldstone Senior RF man (and possibly, by now, the Director of the Pioneer station), stands at centre, wearing a bow tie. To the left, arrowed, is Walt Larkin, the Goldstone Complex Director, and to the left of him is Eberhardt Rechtin, Program Director of the Deep Space Instrumentation Facility. Photo: NASA/JPL Caltech. Image slightly enhanced. |

When the DSN’s ‘second network’ was established, Walt sent a message of welcome to the team at DSIF-42 Tidbinbilla.

Audio – click to hear a 35 second clip. Walt Larkin is one of those to send greetings to the crowd gathered for the opening of DSIF-42, Tidbinbilla, March 1965. Picture: Edmond Buckley and Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies at the Tidbinbilla opening. |

Walt was now Complex Director, but by the end of 1968 felt it was time to move on. Educational opportunities for the children were limited in Barstow, and another challenge awaited.

Australia

Walt accepted the position of JPL Resident in Australia, succeeding Dick Fahnestock, who’d been in that role since 1963.

Walt remembered,

“In January 1969, Pat and I packed up the house, took the children out of their schools, and headed to Australia. We sailed on the P&O liner Arcadia from San Francisco harbor, complete with a band playing on the quayside. We had 28 days to relax, reflect and plan for the next challenge.

We arrived in Sydney Harbour on the Australia Day long weekend; a whole new world. We immediately headed for Canberra, and all five children were enrolled in time to start the new scholastic year in February.

Although my office was in Canberra, I spent half of my working time in Woomera, South Australia [at Island Lagoon]…”

Walt was present in Australia for Apollos 9 to 17, all of which were supported by Honeysuckle’s ‘Wing’ at Tidbinbilla.

He was present for the Mariner 9 mission to Mars, which was supported by Island Lagoon.

He was present for the groundbreaking ceremony in December 1969 for DSS-43, the big antenna at Tidbinbilla, all the way through to its commissioning in 1973.

Walt Larkin, arrowed, at the groundbreaking ceremony for DSS-43, Tidbinbilla, December 1969. JPL Director Dr William Pickering is addressing the crowd. See a PDF file with (some of) the guests identified. Photo from Clive Jones via John Heath. Scan: Colin Mackellar. |

Walt was also in Australia for the closure of DSS-41 Island Lagoon as Australian DSN operations focussed on Canberra.

Walt and Pat in Canberra, 1971. Photo courtesy Kathleen Larkin du Plessis. |

South Africa

In 1974, Walt became the JPL Resident in South Africa, playing a similar role to the one he had in Australia.

Sadly, this included the closure of DSS-51 station in June 1974, as the DSN activities were transferred to Spain.

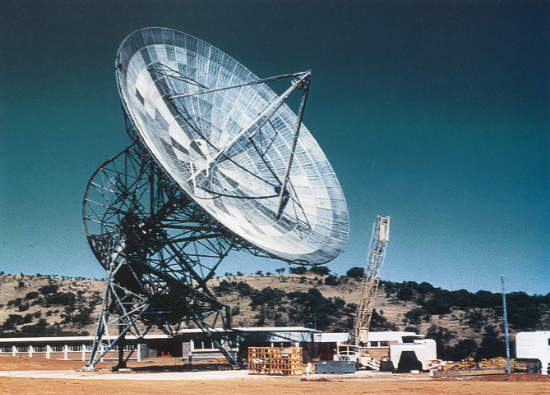

DSIF-51, Hartebeesthoek, near Johannesburg, South Africa. Erected between January 16 and March 25, 1961. Original L-Band configuration. The station is still in use by the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory. Photo from Picture Album of the Deep Space Network.. |

Walt remembered,

“The local personnel were accommodated as best we could and the station shut down. These were times of great political unrest around the world regarding the political situation in South Africa.

The station there had wonderful workers and played an important role in the lives of its employees. It was efficiently run, its staff highly thought of and the government officials I dealt with were the easiest and most pleasant of all my assignments. Housing for the black workers’ families was supplied and a school built just for the local children. It was very difficult to be involved with this closure.”

Australia again, and then Retirement

The Larkins returned to Australia in the 1980s. In Walt’s absence, Phil Tardani and then Doug Mudgway had been the JPL Residents in Canberra.

Walt again took up the reins of JPL representative, completing his role in Australia a second time in 1986, when he returned to JPL at Pasadena. He retired in 1987, after 32 years of service.

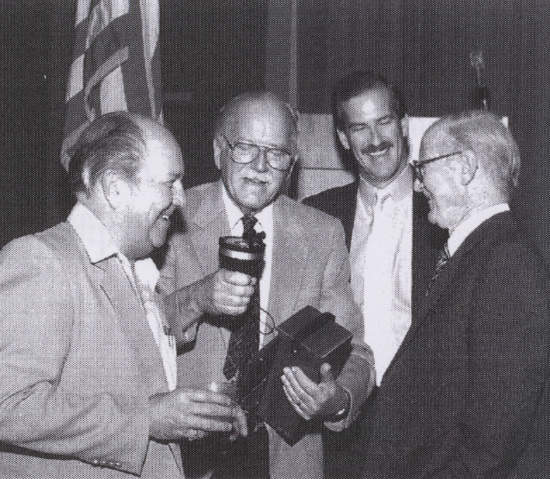

Walt’s retirement party at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California in 1987. L to R: Bob Latham, Walt and Blake Larkin and Dr William Pickering. Photo courtesy Kathleen Larkin du Plessis. |

In retirement, Walt and Pat spent a great deal of time in Australia, including a year sailing around the Great Barrier Reef on their yacht, Solitary Man. After that, they divided their time between Arizona and Sydney. Daughters Maureen and Kathleen had both married and were living with their husbands in Australia, so this was an added incentive to make extended visits.

At a reunion of Goldstone space trackers in 2006, Walt was presented with a blanket and plaque inscribed ‘Mr Goldstone’.

Pat died in 2005, and Walt in 2007. Both chose to have their ashes scattered on Sydney Harbour, such was their affection for the land they came to love.

Walt’s daughter Kathleen remembers her father as “a fine and honourable man” and “a pillar of strength and dependability”.

He is also remembered as a pioneer of the Deep Space Network.

___________

With much thanks to Walt’s daughters, Maureen and Kathleen for all their help. In particular, thanks to Maureen for the loan of several photos to scan, and for a copy of Actually, I AM a Rocket Scientist, Walter Larkin’s memoir completed by Maureen’s sister Kathleen in 2008.

Colin Mackellar, December 30, 2023.

___________

Herb Younger joined the DSN in 1965 and has many happy memories of Walt. He shares this (December 2023):

“Gerry Levy used to come up to Goldstone frequently to do radio astronomy, usually at DSS 13 (Venus). After one long weekend, a security guard checked the refrigerator at Venus and found some beer, a prohibited item at Goldstone. He reported Gerry to Walt.

Walt called Gerry into his office and dutifully told him what a bad boy he had been. He ended the reprimand with ‘next time, put a lock on the fridge’.

Walt had a closet in his office. Inside the closet door, he had a very large (probably 16x20 inches) copy of Walt Victor’s very scary badge photo. When he really wanted to reprimand someone, he’d open the door.

When I was a COE (cognizant operations engineer), I used to correspond via message with my counterparts at the other stations. This was long before email. Walt saw (or at least had access to) the messages, so he always knew what we were up to. As long as he was happy, we never heard from him. (I was usually OK, but he wasn’t always happy with some of the other guys). I loved that management style and tried to emulate it once I got into management: make sure the troops know what to do, and then leave them alone as long as they're doing it.”

___________