Kaz Kijak – Honeysuckle Creek

1919 – 2011

Kaz Kijak at the Apollo 11 35th anniversary lunch at The Canberra Club in Canberra, 21 July 2004. |

Kaz Kijak was a valued member of the Honeysuckle team, serving in the Powerhouse and “keeping the lights on”.

At Kaz’s funeral in January 2011, his friend Alan Scheckenbach spoke about Kaz’s life.

The text below is adapted from Alan’s notes with grateful thanks.

__________

Kaz was born in 1919 in western Siberia, the first son of his father, Wladek a blacksmith, formerly in the service of the Czar, and his mother Zofia, the daughter of a southern Ukranian Gypsy chief.

In the winter of 1921/22, his parents took Kaz and his younger brother Ludwik out of Russia on a moderately epic journey by rail and foot back to his father’s village, Zarudki, in central Poland on the eastern bank of the River Vistula.

Kaz grew up on the farm and rose to the dizzy social height of Polish farm boy. Falling in love with aircraft when an Air Force plane touched down in the large wheat field nearby in the late 1920s, Kaz borrowed all the books he could, on any subject, so that he could learn enough to be able to join the Polish Air Force.

Through the kindly intervention of Pan Pokraka, the head man in his village, he gained a spot in the 1936 intake of the Polish NCO Cadet School at Bydgoszcz in northern Poland. When he got in, he swore a mighty oath to himself, that no matter what, he was going to make good at the school or never come back. He had intended to join a ship at Gdansk and sail the oceans if he failed.

He trained to become a mechanic – although the school tried to make him an air-gunner, Kaz decided to do poorly at that as, if he was going to fly, he was going to be doing the driving. Kaz spent three years there and qualified as a trained aircraft mechanic. Shortly afterwards he was posted to a P37 bomber squadron at Warsaw and was what we would call a crew chief on a particular aircraft.

When the war started they were well outside Warsaw and sent their aircraft on missions against the invading Germans but were continually forced back.

When Poland was also invaded by the Soviet Union, Kaz’s unit was told to cut and run for Romania, which they reached just hours before the border was closed by Russian tanks.

After a trek through Romania to the Black Sea, he and several comrades were collected by Polish agents and – along with hundreds of others – were transported by ship to Syria and then to France, where they eventually made it to Paris. It was here that he and Konrad Szymanski unwittingly changed the course of their lives.

Kaz remembered,

“Only a couple of days later, while we were wasting time in our tents after the evening meal, there came a list, doing the rounds of all inhabitants. It asked for the names of any person who had taken any flying instruction, the hours flown and the name of the flying instructor.

In our group of thirty-two, only three put their names down.

Myself and Konrad Szymanski thought that this was not nearly enough to uphold the honour of our group, so we borrowed an instructor’s name, thought up a believable number of flying hours, eighteen hours and twenty-five minutes, and added our names to the list. The final tally of five looked much more impressive.”

They promptly forgot about that and a few days later were sent to England to be looked after by the RAF.

Then followed intensive English language training, an introduction to cricket, bagpipes and best of all – Wall’s Pork Pies!

Kaz was posted as ground-crew to Polish 316 squadron in the south of England during the Battle of Britain when England was holding on by the skin of her fighter pilots’ teeth. For three or four weeks he was very busy using his trolley accumulator to start the squadron’s Hurricane fighters when they went on patrol or were scrambled to attack an incoming German raid.

When the pressure eased off, Kaz was posted to Brize Norton where there was a large equipment maintenance facility and he and his comrades refurbished tired but essential aircraft ground support equipment.

It was here he met a WAAF, Noreen Laughlan whom he married. It was with Noreen that he had two children – Tony and Pauline. Sadly, the marriage did not last.

However, shortly after Kaz and Noreen were married, that little stunt in Paris about ‘flying hours’ came home to roost and Kaz was instructed to join a pilot’s course in Scotland. With some considerable effort, and calling upon what he already knew, Kaz learned to fly, graduated from the course, and was sent on to gain experience with single-engined fighters.

In late 1943 Kaz was posted to Polish 315 Squadron, arguably the most famous of the wartime Polish fighter squadrons. He flew the legendary Spitfire in combat against serious opposition – the Germans.

He flew quite a few missions over France before the Squadron transitioned to the new Mustang III. Kaz was glad to leave the Spitfire, and its limited range and no heater, behind. The Mustang had range, firepower and speed. It was his favourite fighter.

Kaz flew a dive bombing mission on D-Day – a coveted mission. He flew long-range bomber escort missions deep into Germany. And they flew ground attack missions on whatever German targets they could find. Kaz was awarded a Mention-in-Despatches for hitting a ground target by fluke with a bomb which he was only trying to get off his wing. Something he used to laugh about. He also flew patrols waiting for V1 flying bombs to come over from France. He managed to knock down two.

On 18th August 1944, Kaz was flying with the squadron when they attacked a large number of German aircraft who were taking off to intercept Allied bombers. On this flight, 315 squadron shot down the most enemy aircraft in a single mission during the entire war and Kaz was credited with one shot down and one damaged.

In late 1944, 315 was transferred up to Scotland for a rest and, along with 316 Squadron, they escorted aircraft of 133 Strike Wing to Norway for anti-shipping strikes.

In January 1945, 315 was transferred south again and it was bomber escorts over Germany. Still dangerous work.

In February Kaz had completed a tour and was posted to a training squadron where he taught pupils the finer points of aircraft handling. He was there when the war ended. He did not return to Poland since it was under Communist rule and was likely to have been imprisoned at best if he returned.

Eventually Kaz was demobbed and studied hard for his civilian pilot’s license, gaining it in 1946. He worked for several companies and in 1948 settled into aerial photographic work. It was here that he met Eileen for the first time, and their relationship soon blossomed. When the aerial photography company Photair failed, Kaz took up work as a milkman – and then worked as an ice-cream-seller while waiting to rejoin the RAF.

In late 1949 Kaz joined the RAF and was trained on multi-engined aircraft and flew the Wellington, a wartime medium bomber, still in service but no longer a front-line aircraft. It was his favourite bomber.

After getting through all the familiarisation Kaz was posted into Transport Command as a second pilot and flew in Hastings transports down to Africa and Egypt and even out to Singapore. There were some very long flights. He was then posted to 7/76 bomber squadron where he flew the Avro Lincoln, the development of the famous wartime heavy bomber, the Lancaster and formed part of the deterrent to the Russian threat against Europe during the early part of the Cold War.

Kaz was one of the few pilots given the task of flying formation at the new Queen’s Coronation in 1953 – after which he took some time off and married Eileen. And went on a short honeymoon.

Kaz was nearing his flying use-by date by now and was posted to the Bomber Command Bombing School to pass on his accumulated experience to the young ones coming through.

About a year later later, Carol was born to great celebration at the Kijak married quarters on RAF Lindholme, followed by Christine in April 1956. In June 1956, Kaz’s posting to Seletar in Singapore came through and he left Eileen with the girls and was flown to Singapore. Eileen and the children followed by ship several months later.

Seletar was Kaz’s last flying job and a lovely time for the family. There was a motley collection of aircraft in the base flight and Kaz flew Beaufighters – the same as he escorted to Norway during the war, as well as jets and was pleased to have been able to break the sound barrier a couple of times.

Kaz was asked to apply to be an officer several times during his career but turned it down every time as he couldn’t see himself as an officer. In 1959 he was posted back to England and the family set off by ship back home.

Kaz was sent on an administrative course where he learnt the ins and outs of running RAF establishments and was then sent to Bircham Newton and Hawkinge as Station Warrant Officer. People like Kaz were valuable in terms of their accumulated knowledge and formed the backbone of the administrative structure of the serious militaries across the world. After a couple of years of that work he was posted up to RAF Acklington where his long years of flying experience were used to train young pilots from all over the Commonwealth in blind flying techniques.

In 1964 Kaz’s Air Force career ended with his retirement but only after he completed RAF transition training on earthmoving equipment.

After a short stint selling garbage trucks, the family emigrated to Canberra where Eileen’s sister and brother were living.

Kaz turned his hand to a number of jobs in the fast growing Canberra before finding himself work as a powerplant mechanic at the new Honeysuckle Creek tracking station being built for the Apollo missions.

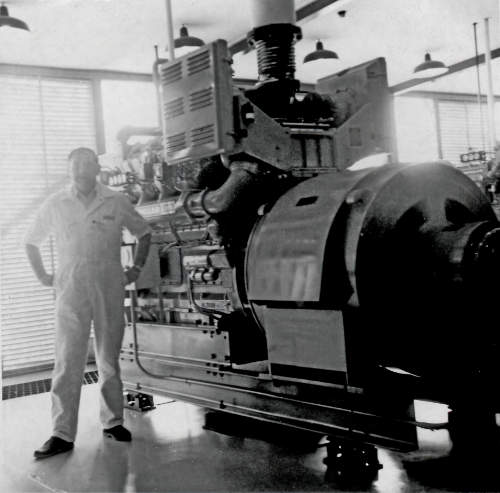

Kaz Kijak in the Honeysuckle Creek powerhouse. Scan by Alan Scheckenbach. |

He was on rotating shiftwork making sure power was supplied reliably to the dish and computers in the complex.

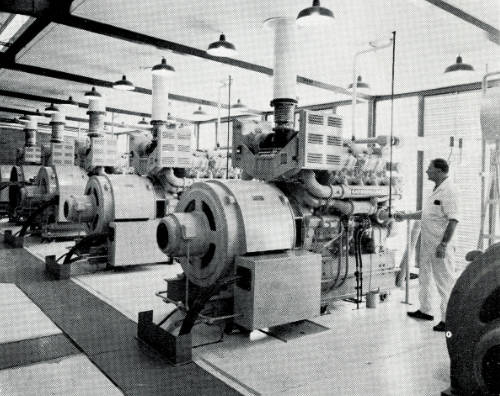

The Powerhouse – bank of diesel generators c. 1966. Seven diesel alternators supplied more than enough electric power for the whole station. The diesel engines were manufactured by Caterpillar with power capacities ranging from three 500 kVA units, two 350 kVA units and two 250 kVA units. Photo: Ian Hahn. |

Kaz Kijak in the Powerhouse, 1967. From an STC publication, April 1967. |

Kaz was very proud to have been on duty and supplying power when Neil Armstrong set foot on the moon on 21st July 1969.

The Honeysuckle Creek powerhouse in winter. Photo: Kaz Kijak. Scan: Alan Scheckenbach. |

He worked at Honeysuckle until the end of 1981 when the station closed and he officially retired.

From then on, Kaz enjoyed some travel around Australia with Eileen, they moved down to the coast at Tuross. After four years they moved back to Canberra to be closer to family.

Kaz had a knee and hip replacement in the early 1980s. The inserts were German steel. He used to laugh that the Germans had tried for the entire war to get their steel into him but they only managed it after he gave them permission!

In the last ten or so years Kaz met a number of people who fought during WW2 and was pleased to be able to roll those hangar doors back and roll out the war stories over a couple of beers. He really enjoyed the lunches at the Yacht Club on the lake.

In the last couple of years Kaz also managed to contact his family and his old primary school in Poland and close the circle of uncertainty of what happened to his family during the war years and while Poland was behind the Iron Curtain.

Pleasingly the school commemorated his life and rightly honoured him as a war hero. That is no exaggeration.

________

With very special thanks to Alan Scheckenbach for sharing his notes on Kaz’s story, and also his photos.