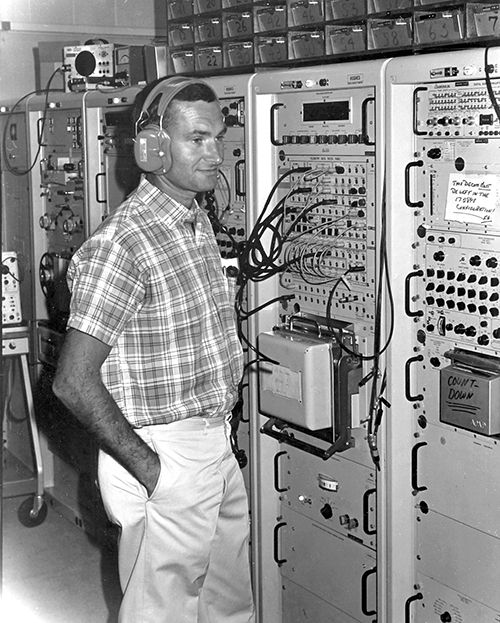

John Flaxman at Tidbinbilla in 1966.

Note the handwritten sign, “This Decom must be left in the 17.2BPS configuration! – F.H. [Frank Hain, Hughes Surveyor team]”.

Photo: Les Whaley. Scenned by Mike Dinn.

John Flaxman

Tidbinbilla

Although it doesn’t seem to show up much in books or television programmes about NASA space adventures, the ‘Surveyor’ spacecraft was all the rage when, after Blue Steel, I joined Bob Cudmore, Alan Bailey, Dave Arman, Roy Stewart, Jim Wells, Pat O’Connor and Co. at Tidbinbilla Deep Space Tracking Station, near Canberra.

It was run by ‘SpaceTrack’ a consortium of several companies, one of which was Elliotts.

Surveyor was an unmanned craft destined to touch ‘gently’ down onto the moon (in fact it sometimes bounced a few times) and send back to earth such good things as TV pictures, telemetry and data from soil samples obtained by digging holes with an on board scoop. It was quite a contraption.

The great thing about this spacecraft was that it was manually controlled from earth, unlike more recent projects where the tracking stations have become more like relay facilities, passing on the data directly to the States with little interference from the locals.

John Flaxman at Tidbinbilla in 1966. Note the handwritten sign, “This Decom must be left in the 17.2BPS configuration! – F.H. [Frank Hain, Hughes Surveyor team]”. Photo: Les Whaley. Scenned by Mike Dinn. |

Then, it was different – you sat at a console and pushed buttons to physically move the camera, change the focus or dig a deeper hole with the soil sampler – it was real hands-on stuff and you could see the results almost immediately on the telemetry panel and the TV screen.

I remember returning from the States with the Hughes Aircraft crew and getting the Surveyor mini-control room installed and set up. Then followed seemingly endless count-downs and rehearsals, some of which were run from J.P.L. in the States. These latter were extremely comprehensive simulations of different phases of the mission, from count-down, launch and cruise through to injection and finally touch down.

It was all go in the Surveyor area – every time a different set of information was needed it was necessary to change telemetry commutators and bit rates and this involved a fair bit of manual effort, like unplugging patchboards and discriminator units (rather like Tektronix plug-ins), inserting new ones and then adjusting the decommutators to re-synchronise the bit stream and finally, selecting the correct overlay (usually from a pile on the floor!) for the telemetry read out panels, so that the meters and digital read outs were correctly labeled and scaled. All this meant actually walking around and lifting things – no computer screens to veg out in front of in those days! And get this – the telemetry display unit included a row of beautiful analogue meters – you could turn something on or off on the spacecraft and actually watch the needles move – fantastic.

You can imagine the atmosphere in the control room when, for the first time ever, Man was going to act the tourist on the Moon’s surface and start taking pictures. The command was sent to turn on the camera, then a few more to adjust the focus and then there it was – the first ever photograph taken on the Moon. Instead of the little green men we were all secretly hoping for however, there was nothing but a barren, rocky desert very much like some parts of Central Australia. – a bit of a fizzer really!

We took lots of Polaroid pictures of our TV screen as the camera was panned across the lunar scenery, and laid them out on the floor to form a mosaic. The more pictures we added the more impressive it became. I thought I’d stir things up a bit by inserting a cropped photo from one of our recent trips up the Birdsville Track – the terrain matched the lunar surface perfectly but for one small detail – it had a few old bones lying around in it! It was a little while before they were noticed and I heard some important people who were visiting the station making remarks like ‘they ARE bones – just look at THAT’ and so on. Soon the discussion got rather heated as excitement rose rapidly and since there was a gentleman from the press present I thought it better to own up before the situation got out of hand. The aforementioned visitors were not very impressed at first (were they Bob?) but after things had quietened down a little we all had a good laugh.

It was a great experience and I’m glad I was part of it just at that time – after Surveyor things on the telemetry side became more automated and people almost vanished from the loop, their main function being relegated to pointing the antenna and locking on to the spacecraft, after which the data flowed directly to the States. Since it was their data, this was fair enough I suppose, but the overall task was not quite as stimulating; the ‘hands on’ atmosphere was no longer there.

Just a couple of memories for what they’re worth.

Soon after I joined the tracking station, the Mariner spacecraft was about to arrive at Mars and the papers were full of stories to the effect that, since our antenna was pointing directly at Mars, and if there were Martians, this would be the time when they would detect our radio signals and fly back down the beam to see where they came from – wow! Although we weren’t tracking that night, we were counting down for an early start, when we had an urgent call from the canteen, sited some distance from the main building and an excited voice told us to come quickly and hung up. We thought the place must be burning down but when we arrived we found all the kitchen staff lined up outside, watching some very mysterious lights moving around in the sky and dodging behind the hills. Considering all the media hype and the somewhat tense atmosphere surrounding the pending arrival at Mars, this was indeed a strange phenomenon and we were all extremely puzzled, if not excited. The truth was somewhat less sensational, however – we found out later that the lights were on a helicopter doing some calibration runs for Honeysuckle Creek, a tracking station a few miles away, and were definitely not flying saucers!

One Apollo mission ‘The Tid’, was assigned the task of tracking the main spacecraft (the CSM) as it orbited the Moon waiting to pick up the space tourists, while Honeysuckle looked after the LEM as it sat on the Lunar surface. Unfortunately the dreaded lurgy struck the crew and the shift began to wilt as, one by one, we all succumbed to this particularly nasty bug. Manfully we struggled on and fronted up each day, coughing and sneezing a bit more than before as reporting sick was just not on. The mission was in a critical phase – return to earth – and a whole shift gone AWOL could have been disastrous. The last shift finally came and the bunch of characters who showed up were not at all a pleasant sight to see – not that we were anything extra special normally, but this day, boy, we were rough!

However, every cloud has a silver lining they say and so it was for us – I can still see in my mind’s eye, the image of Bob Cuds roaming the Ops. Room clutching a bottle of brandy and fortifying the troops for this last big effort. Somehow we all finished the shift (as well as the brandy) and departed for home a good deal happier than we started – nice one Bob!

Many exciting things happened while I was at ‘The Tid’, but I suppose the most memorable of all for me was when I met Sylvia – but that’s another story. (I had to put that in somewhere or I would have been in deep trouble!)

Originally written by John for the “Blue Steel” reunion book.

At one of the Apollo 11 anniversary reunions, John and his daughter, Mandy, were interviewed by A.B.C. reporter Adam Shirley. Listen, courtesy John Flaxman and ABC Radio.

|

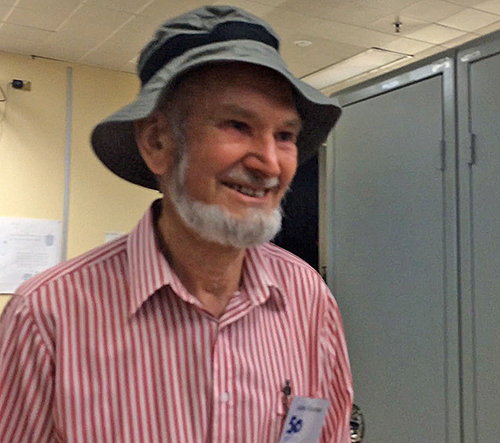

John Flaxman at Tidbinbilla in March 2015 for the 50th anniversary of station opening. Photo: Colin Mackellar. |