Chuck Koscielski worked at Goldstone for 25 years, leaving the DSN to become SFOF manager in 1984.

He spent a great deal of time at Woomera, DSS41, and was there for the opening of the station, and was later the JPL lead for the S-Band conversion.

Chuck became the Asst. Station Manager at DSS-11, the Goldstone Pioneer Station, and was DSS-11 Station Director during Apollos 7 to 17. He became Goldstone Operations Manager in the early 1970s.

Chuck has kindly shared some memories of DSS-41 and his trips to Australia –

Chuck Koscielski and DSS-14. Chuck Koscielski and the then 210 foot (64 metre) Mars dish. |

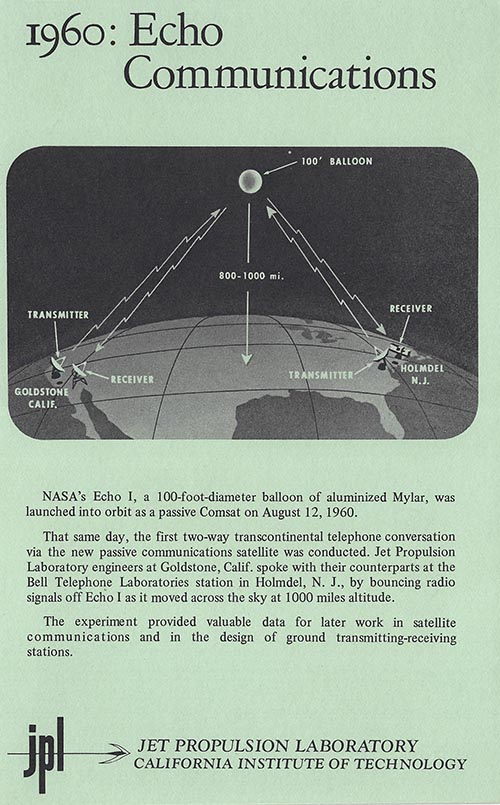

NASA was planning a spectacular mission in a year or so. This event would involve placing a 100 foot aluminized balloon into Earth’s orbit. Ground stations would transmit signals to bounce off the balloon to stations far away. This process allowed communication across the US.

In order to test the ground stations, it was proposed to use the Moon for a test of the equipment. This project was appropriately called Moonbounce. The Moon is not a smooth surface like the balloon, but the scientist thought it could be used.

I got involved with the transmission part of the project right from the start.

Tom Potter and I were sent to Bell Laboratory facility in Holmdel, New Jersey. We made the trip to the facility that would be used as the sending link for the signal to bounce off the surface of the Moon and would be received at the Goldstone station.

It was a thrill to work with some of people, at Bell Labs, who were some of the leaders in the field of communication. Some of these people had written the text books we used in college classes. We tested the system with a degree of success. It all worked well enough that the link was used to broadcast a message from President Eisenhower to the people of the US.

WOOMERA

Since things went well enough with our Moonbounce experiment, NASA decided we should do it again, but this time with the new station in Australia.

Australia was chosen as second location for an antenna because spacecraft launched from Florida would be seen over Australia first.

I built the radio receiving equipment that was needed and took it to Australia. To accomplish future US missions, a second 85 foot antenna was built at Goldstone. This station was equipped with a high power transmitter that would be used to transmit for the 100 foot balloon project. The name selected for that project and was, Echo, the name given to the new station was therefore, the Echo station.

The Echo station, as viewed from Goldstone’s helicopter. Photo by Pat Delgado. |

The Echo station was outfitted with a 10 KW transmitter which would be used to send commands to future space missions but would also be used to send a welcoming message to Woomera, Australia.

The Australian Station was located in the state of South Australia, at a place called Island Lagoon, on a military base and missile test range called Woomera. A Woomera is a wooden Aboriginal spear-throwing device. Founded in 1947, as the home of the Anglo-Australian Long Range Weapons test establishment, it was named after the spear.

In February, 1961, I arrived at the station and met the crew and began a series of long friendships.

John Duncan was the technical lead, together we installed the equipment I had brought over, and tested it. It worked well and we waited for the big day.

On February 11, 1961, NASA Deputy Director Dryden spoke to the Director of the Department of Supply, the Australian organization that would operate the Woomera station.

When the time came, the transmission was as clear as a bell (if you had a noisy bell). The Australian person would be able to talk to Dr. Dryden in Washington, DC by a regular overseas land telephone line, which took several seconds for the conversation to take place. It was declared a success and was all over the Australian newspapers.

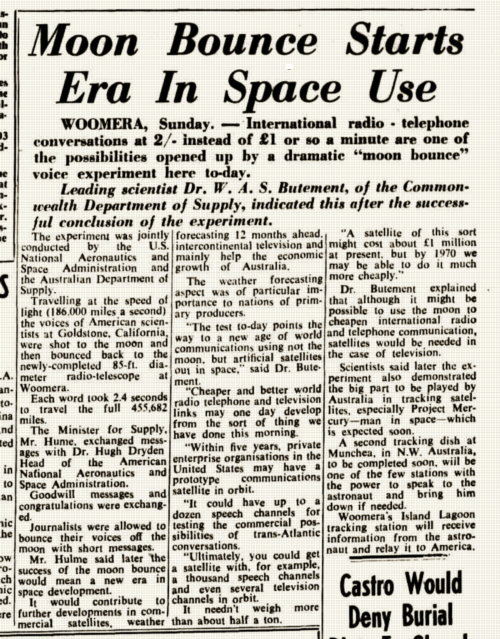

Here’s a report on the front page of The Canberra Times, Monday 13th February 1961. |

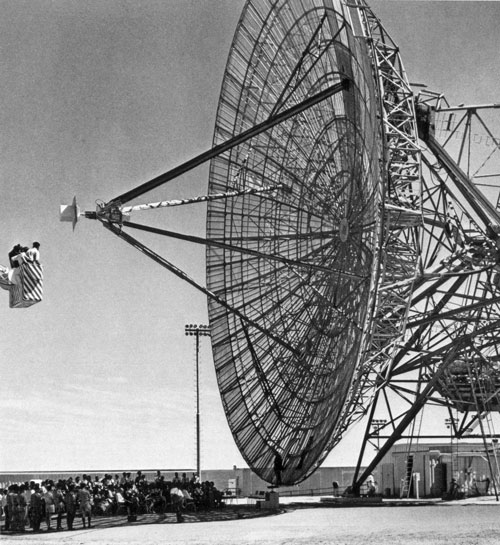

A photo of what appears to be the opening ceremony of DSIF-41. This photo was found in “Two Centuries”, published by the Australian News and Information Bureau in 1970. The crowd is being addressed by someone standing on the edge of the dish. |

This was to be the first of my five trips to Australia, over the next four years.

Goldstone

Back at Goldstone, we began to prepare for the ECHO project.

The Echo balloon would be launched into Earth’s orbit. It would inflate and be used as a reflector to allow long range communications between the east and west coast or even between continents. It was very visible in the sky as a bright object moving from west to east. It would have a short life, but, would serve until first communication satellites could be launched.

Thinking back to this project, in the current digital era, hundreds of satellites are literally circling the Earth. This effort seemed to be a baby step to today’s technology.

Chuck Koscielski writes, “I have lots of Echo memories. I was the transmitter tech at the time Echo was started. I built a modulator and took it back to Bell labs in New Jersey and ran tests with Goldstone to prove the concept by bouncing signal from the moon. It turned out the moon was not very smooth and not friendly with my phase modulated modulator. Bell labs had a FM modulator which work better so it was decided to use it. Woomera was nearing completion at that time so NASA decided to make some news by opening Woomera with a Moonbounce.” Les Whaley (Tidbinbilla) preserved this snippet from a JPL publication. Scan by Colin Mackellar. |

Let me mention some of the people I worked for and with at Goldstone. Many were great mentors to whom I owe much gratitude to Howard Olsen, Tom Potter, Jack Buckley and many others. I learned a great deal and was fortunate to have been given opportunities to succeed. It was all work that I loved and into which I put my heart and soul.

A transmitter for Woomera

In the next two years the Deep Space Instrumentation Facilities (DSIF) grew and supported Ranger missions to the Moon. There were now two stations at Goldstone and one in Australia. A new station was being built in South Africa, outside of Johannesburg. The four facilities were located about 120 degrees apart, two north of the Equator and two south of the Equator. This insured that one station was always in view of a spacecraft. These stations were originally known as the DSIF until they became known officially as the Deep Space Network in 1963.

The first six Ranger missions (1961-1964) failed to return data and pictures of the Moon’s surface. Finally, in 1962 Ranger 7 was successful – as was Mariner II to Venus.

In 1962, I was given the task to build a low power transmitter for the Woomera station. The station would be the first to see several planned deep space mission launches. JPL had developed the use of two-way tracking at launch. A single station would transmit and simultaneously receive signals from the spacecraft resulting shift in frequency called the Doppler Shift which is used to determine the location and speed of the spacecraft. So, Woomera would need a transmitter.

DSIF-41, Island Lagoon, 14th December 1961. This is the original L-Band configuration. |

I took the equipment I had built, to Woomera, installed and tested the new capability. It all worked well and was used during the Mariner II mission to Venus, several Ranger and future missions. My little transmitter worked well until it was replaced by a high power system installed the following year. The Mariner II to Venus success provided new information about the planet.

After finishing my work in Australia, instead of returning directly back to the US, I took vacation and flew from Sydney to Tokyo and spent two weeks with Edi and John who were visiting her family, in Japan. It was a wonderful time. A great opportunity to visit Japan again.

In 1963, it was time to install a more powerful 10 KW transmitter at Woomera. This would provide the station with the capability to send commands and communicate with current and future missions. Since I had taken on the responsibility for the 10KW transmitter at the Echo station, I had the task of overseeing the installation at Woomera.

DSS-41, Island Lagoon, c. 1963. This is the original L-Band configuration which was used mainly for the Ranger missions. Photo via Don Gray. Scan: Colin Mackellar. |

Howard Olsen and I had another task to standardize the overseas stations to Goldstone stations. This was known as the Goldstone Duplicate Standard. It was an attempt to make all the station’s documentation and equipment look the same.

Since it was close to the time for NASA (JPL) to launch the first attempt to send a space probe past the planet Mars, (there would be two separate launches), I was told to stay a few more days in Australia to see the launch and to be certain everything went well.

This mission was to fly past Mars and take a few rudimentary pictures. The first launch went well but a problem developed when the nose cone failed to come off the probe, rendering the project a failure.

I came back to Goldstone after the Mariner 3 failure and began to work on a system that NASA wanted to locate at a very large astronomy antenna, at Parkes, Australia. This 210 foot antenna was one of the largest in the world at the time. NASA wanted to use it as a backup when the next Mariner Mars mission reached its target… Mars.

Woomera and Parkes

A week after arriving back at Goldstone, I got a phone call telling me I was going back to Woomera. We had experienced a problem during the first mission to Mars.

The problem involved the frequency stability of the ground equipment. The frequency stability is very important to the people that must figure out how to correct the path of a spacecraft leaving Earth, on the way to Mars. Hewlett-Packard had developed a special piece of classified equipment for the US Navy to use with the Navy submarine fleet. This equipment offered a solution to a frequency stability problem. Woomera would be the prime station for the launch and the early part of the upcoming Mariner 4 mission, a repeat of the failed Mariner 3 mission.

The decision was made to rush the equipment to the station, I was told to personally carry the equipment, called a frequency synthesizer, to Australia at warp speed.

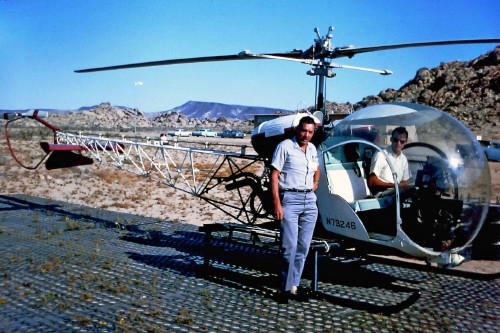

I had to move quickly and Edi was a big help. The JPL helicopter picked me up at Goldstone.

Pat Delgado with Goldstone’s helicopter, during the Island Lagoon team’s visit for the L to S-band conversion. Scan: Jan Delgado. |

We flew to Barstow, close to where we lived at that time. Edi met us at an empty lot, not far from our home. She had my passport and packed a suitcase for my trip. I kissed her and John goodbye. From Barstow, we went by helicopter to Daggett airport just a few miles from Barstow. There, I met the JPL plane and flew to Burbank airport.

I met Jim Wilcher at Burbank, along with a large box. Jim had persuaded HP to persuade the Navy to declassify the equipment. My orders were to not let the box, containing the equipment, out of my sight.

The JPL plane flew me and the box to San Francisco airport. That day it happened there were no flights out of LAX to Australia.

I managed to catch a Qantas plane for the flight to Sydney. On the plane I had a seat in coach with my large box in a seat next to me. (The Manifest said the seat was occupied by Mr. Box.)

When I arrived in Sydney I was met by the JPL representative in Australia, Richard Fahnestock. He had chartered a small plane that flew the box and me directly to Woomera, a flight of about 1000 miles. This is probably the quickest trip anyone had made from the USA to Woomera, at that time, in less than 30 hours, as I recall.

I got to the station, installed the equipment and tested it for 72 hours. All this time I never got a chance to check into my room or go to bed, but I managed to find some interesting places to nap at the station.

JPL declared the test as a complete success.

Bill Mettyear, left, at DSS-41. In the centre is Dick Fahnestock, JPL Representative in Adelaide. At right is John Haselar, the technical lead at DSS-41. Photo dated 26th July 1964. This is immediately before the launch of Ranger 7 on 28th July 1964. Ranger 7 was the first American spacecraft successfully to transmit close up images of the Lunar surface back to Earth. Scan: Bill Mettyear Jr. |

After the successful launch and support of Mariner 4, I returned to Goldstone to finish the work on the equipment to be shipped to Parkes. Hillary McDonald, was my contractor assistant on this task and a great help in completing the task, preparing the trailer for shipment and writing complete procedures and documentation so that we didn’t even need to go to Parkes. The Aussies at Parkes were outstanding technicians and engineers, the equipment worked well and gathered data and a picture when Mariner 4 passed Mars in 1965.

Our next task was to modify the equipment to frequencies that we would be using on future missions. The project called the L to S Band conversion involved modifications to both receiving and transmitting equipment. This became necessary for future missions that would require more bandwidth to take more and better pictures.

The lower frequency continued to be utilized to support older missions. which were still operating. Jim Wilcher, an excellent engineer, was the Project Manager and I was his assistant for the Woomera installation. Another JPL engineer handled the South African modifications.

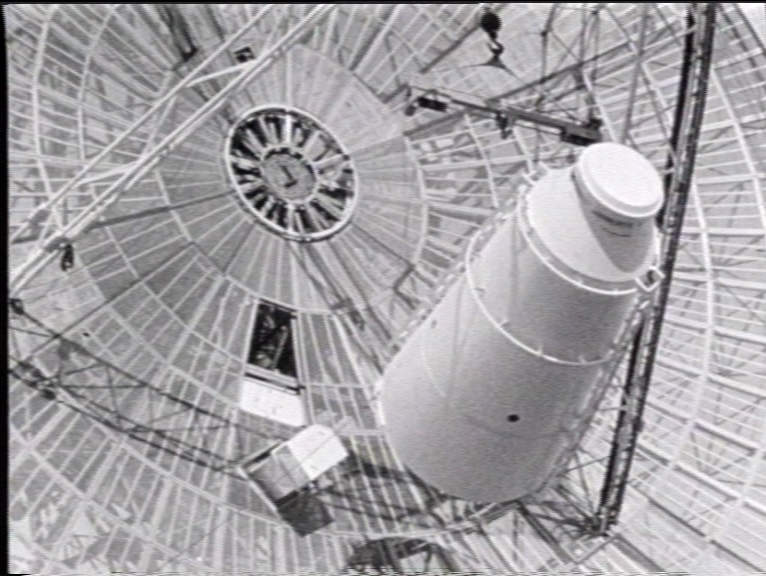

DSS-41, Island Lagoon, L to S-Band conversion. Click the image for a 50 second silent clip of the S-Band feedcone being installed on the dish. Dept of Supply footage, filmed 10 June 1964. |

DSS-41, Island Lagoon, 1966. S-Band configuration. Photo: Taken by Pat Delgado from the cherry-picker. |

At Goldstone, we built a lot of the equipment that was needed not only at Goldstone, but enough to outfit three systems at Goldstone, two overseas, one in Florida and one in Pasadena. I had a crew of about ten contractor personal who did most of the work. The work was completed and in 1965. Olsen and I made another trip to Australia to oversee the installation of the equipment. The entire project was successful and the equipment stayed mostly unchanged for the next 10 years or so.

As it turned out, most of my trips to Australia coincided with the Queen’s birthday (Queen Elizabeth of England, of course) The Aussies always have a celebratory event which includes dinner and a dance with an imported band. A real rarity for Woomera. The dinner was always chicken because in those days chicken was a special feast in Australia. Now, there is a KFC on every other corner, except in Woomera.

This was the time that I met life-long friends, the Grays: Don, Peg and their kids. Don and the family lived in a house we owned in Barstow while they were there for JPL business.

After his time at Goldstone, Chuck became the SFOF (Space Flight Operations Facility) Manager at JPL in 1984 until his retirement. |