With the station operational after the departure of Ray Cox and the Collins installation team, and the Telemetry, Computer and Communications equipment passing all the installation tests, John Talbot, the NASA installation engineer announced the station was ready for tracking spacecraft.

We began our tracking experience by using aircraft. Our first aircraft tracks began on Sunday 11 December 1966 to check out the USB and antenna tracking systems. Using a brilliant light on the belly of a C-121 Super Constellation to locate it in the dark, it was the most accurate way of tracking the aircraft using our boresight television.We began work at 1600 with Jack Kennedy from Collins Radio and Bob Taylor, the NASA Test Conductor, but initially we had a lot of trouble finding the aircraft. Once Roy Benson, our USB Engineer, said triumphantly “I’ve got it!” but it turned out to be one of our own signals on the ground someone had inadvertently forgotten to turn off. After a couple of tracks the aircraft was running low on fuel, so returned back to base in Sydney.

The next day wasn’t much better when cloud came down and we couldn’t see each other at all. When we heard them fly right overhead but their DME and RDF had them 24 kilometres away they decided they were lost and the day’s exercises were scrubbed.

The third day it was raining, so again the tests were scrubbed – but things improved after that.

With our inexperience and troubles trying to find the aircraft at one stage we tried Ian Anderson standing outside the window where we could see him pointing at the aircraft with his arm!!

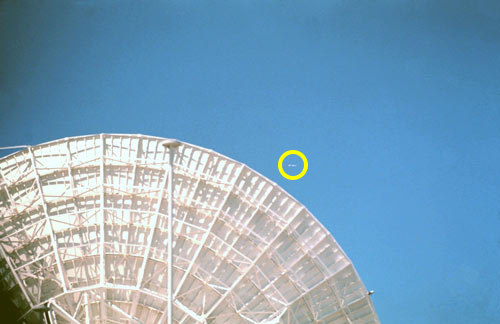

Bruce Withey took this photo of the Honeysuckle antenna tracking Super Constellation NASA 421 |

It was a time of UFOs and Canberra residents rang us on the telephone in droves querying if this bright light ranging back and forth south of the city was a UFO or flying saucer. The same light and aircraft were seen as flying saucers by the Americans in March 1967 when flying over the Goddard Space Flight Center’s Test and Training Facility in Maryland.

Ops Supervisor John Saxon:

Looking forward to our first Apollo mission with Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee, we were all stunned by the news of a fire killing all three astronauts on 27 January 1967 during a countdown simulation test at the Cape. We knew this would put the brakes on the project for a long time, and realised it would give us plenty of time to prepare for the first Apollo manned mission, but we did wonder about President Kennedy’s 1969 deadline...

On 10 June 1967 we had our first Apollo simulation with the network, beginning at 1900 AEST.

It began as a bit of a shambles but began to settle down as we went through the night. It was a long spell for us, as we didn’t finish until 1500 the following afternoon. The Station Director held a de-briefing in the computer room and I cringed when he said we had been asked to support another simulation the next night. “I told them we would not support it as we had been up all night and we were all too tired.” In those days at Honeysuckle, I had just come from Carnarvon and was the only person with previous experience of MSFN procedures. I knew you NEVER, NEVER told NASA you were too tired to support any of their requests.

On 20 June 1967 we adjusted the antenna sub-reflector focussing using the signal from the Lunar Orbiter spacecraft. I operated the X-Y recorder while Jim Kirkpatrick and Ian Anderson went up and down in the cherry picker with spanners to move the sub-reflector up and down. In the end we only moved it 1.6 millimetres!!

The next day, Wednesday 21 June 1967 George Harris and the Goddard Simulation team arrived in the Super Constellation NASA 421 to check our mission procedures out. In the USB area we had Rod Fischer as observer, helped by Jerry Brennan. First of all we did a Phase 1 Site Readiness Test (SRT) which we were to become very familiar with, as we had to perform one before every manned flight pass. There were lots of conferences and discussions between the hierarchy but we troops had little idea of what was really going on, except to know we were not doing very well. This was made very clear to us at a meeting in the crew room.

On Sunday 9 July, the Goddard team’s last day, we tried an H-140 count, beginning with a Phase 1 and 3 SRT before going into a pass. Then we did an H-30 count which was full of drama as the Sim Team observers made Brian Bell, the Servo Operator controlling the antenna, have a sudden attack of appendicitis and Paul Mullen, sitting alongside making notes, had to jump into his place. USB Engineer Mike Evenett replaced Paul.

The Chief Engineer, Wes Moon, was in the chair as the M&O (Maintenance & Operations Supervisor), which Mike Dinn later changed to the simpler titles of Ops 1 and Ops 2, but Wes was having a hard time getting his time hacks on the right time as well as announcing LOS a minute early.

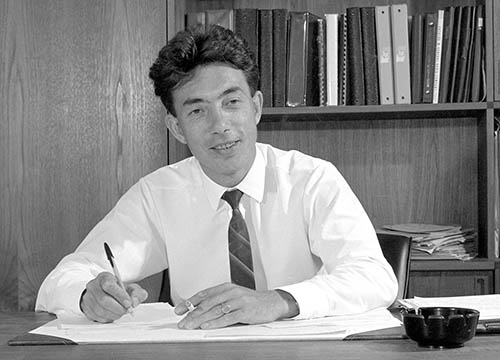

Honeysuckle’s first Station Director, Bryan Lowe. Photo: Hamish Lindsay. Negative scan: Colin Mackellar. |

As a result of our poor performance in these simulations we suffered a major staffing shake up, beginning with a new Station Director.

Tom Reid was transferred from Orroral Valley to replace Bryan Lowe and Deputy Director Bert Forsyth was replaced by Michael Dinn from Tidbinbilla.

On Monday 7 August 1967 Tom Reid arrived, just as the new road was opened, and we prepared for a second session with George Harris.

On Monday 18 September 1967 George Harris and the Simulation Team arrived from Carnarvon and on Thursday we had an H-140 count, interfacing with the Wing at Tidbinbilla for the first time. After our previous efforts we all had a better idea of what was required, but Reid very cunningly requested George Harris to be M&O (Ops 1), assisted by Ken Lee as AM&O (Ops 2). This time we followed the procedures a lot better than before. These simulations were so intense that Eric Stallard in Telemetry was asleep in bed at home and, during the dead of night, startled his wife by suddenly sitting up and calling out “Decoms in Lock!”.

After many practice runs NASA 421 and the Sim Team left on Friday 29 September and left us to lick our wounds.

The staff shake out continued with the contractor’s Chief Engineer Wes Moon was replaced by Bill Kempees from Orroral Valley, the company manager John Matthews replaced by Tony Cobden, the USB Engineer Roy Benson by Gordon Carlisle, and Telemetry Engineer Geoff Seymour was brought in from Woomera.

|

|

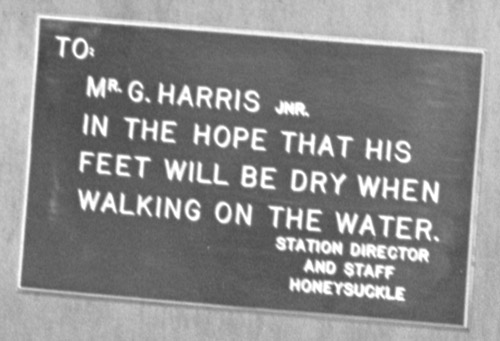

Station Director Tom Reid (left) presented Goddard Simulation Team Leader George Harris with a pair of sandals mounted on a plaque with the inscription, |

|

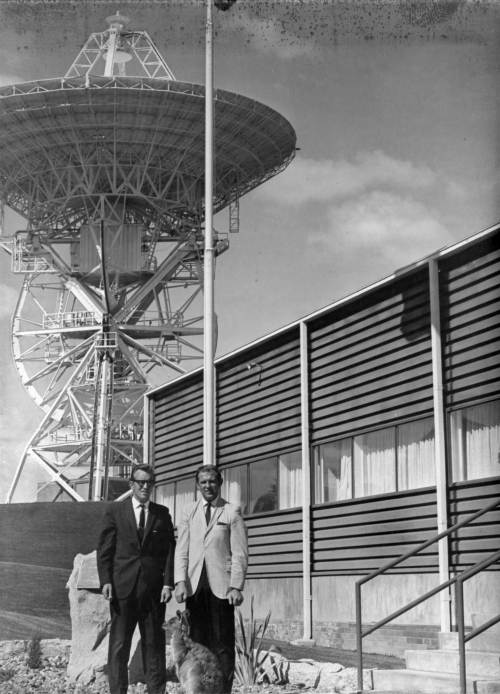

Station Director Tom Reid (left) and Goddard Simulation Team Leader George Harris with the station mascot. |

|

Station Director Tom Reid (left) watches as Goddard Simulation Team Leader George Harris is farewelled by the station mascot. |

We now felt responsible enough to face a real manned Apollo mission.But first NASA had to try out the Saturn V rocket.

We tracked all three of these missions, which gave us good experience working with the MSFN network, and lots of practice acquiring and tracking spacecraft, plus a real live handover in Earth orbit. With all the simulations and real spacecraft tracks we felt we knew our equipment and had developed into a confident team.

The Apollo Flight and Ground teams were now ready to send astronauts into space.

|

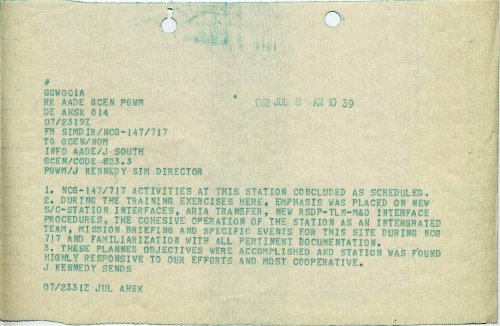

Jim Kennedy, NASA/GSFC Sim Director visited HSK in 1968 and also in 1970. |