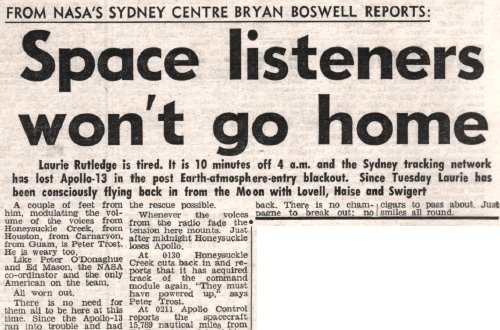

Peter Gabelish, a passenger on the same Air New Zealand flight, was on his way from the US back to Sydney.

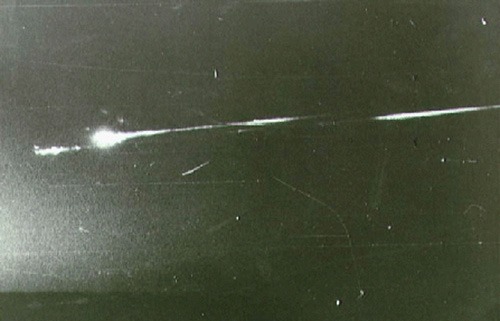

He, along with the other passengers, viewed the re-entry fireball and, a few minutes later, took this photo of the trail left by Apollo 13. The spacecraft travelled from right to left, into the Pacific dawn.

With thanks to Peter Gabelish for his kind permission to use the photo, and also thanks to Bill Keel for the tip.

Update (April 2017): Peter shares his account of the experience:

“I found myself on a southerly flight across the Pacific to Auckland with the vague feeling that our route would be close to Apollo 13’s re-entry trajectory. I was on my way home from a stint in the US and Apollo 13 was big news, particularly in the States, as the three crewmen on board the stricken spacecraft fought for their lives. We were no sooner seated for take-off than a rather excited pilot announced, ‘You may or may not be aware that we are expected to see Apollo 13’s re-entry into the earth’s atmosphere. We are in communication with Houston and will be the first to see the returning spacecraft. Houston want us to remain in contact until vehicle recovery’.

Much excitement on board as everyone who had a camera set it up for the spectacle. Fortunately I had a camera that allowed me to set shutter speed, aperture etc., unlike the average modern camera that won't let you do much except point and shoot. Having figured out what I thought would work I proceeded to advise a fellow passenger on settings. It turned out that he was a professional photographer assigned by a newspaper for the event. I hope he appreciated my advice as my photos came out beautifully on my basic equipment.

With the cabin lights out we waited expectantly. Running about two minutes behind schedule a brilliant fire ball, like a massive Very light [a type of flare] appeared over the starboard horizon! Travelling horizontally, an incandescent, silver plume of brilliant light, leaving a blazing trail of constant width behind it, arced in from the west at an altitude that didn’t appear to be much higher than ours. The silver phosphorescent tail it left behind seemed to retain its brilliance as a curved band of luminescent material while the leading body continued at constant velocity across our path. I presumed the tail to be the vaporized aluminium and magnesium materials from which the capsules were mostly constructed. My reaction was that no one could live through the incredible fireworks and that all must be lost. Every few seconds a bright yellow-orange spark would branch off the main spearhead and arc away on a different trajectory.

The incredible display continued across our path and arced towards the eastern horizon on our port side. The inferno diminished while still within our sight. When it died out, a minute red dot continued on the east bound path, curving out of sight over the horizon. This was the command module with its glowing heat shield that had survived the impossible inferno and miraculously had living humans inside it. I would guess that the whole display lasted three to four minutes.

We were fortunate that the whole re-entry was seen in total darkness.

Several minutes afterwards day began to break and the trail of vaporized metal was visible hanging in the upper atmosphere for the next twenty minutes or so affording me the chance to photograph it as it hung there.

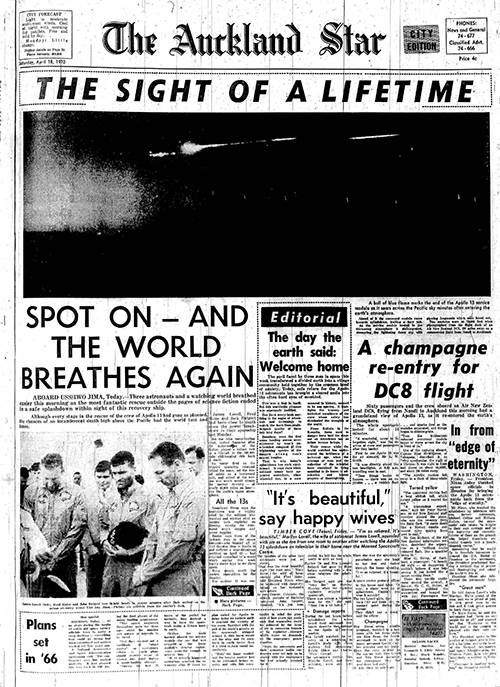

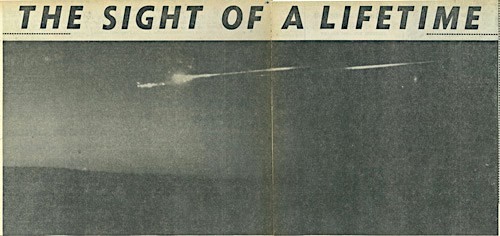

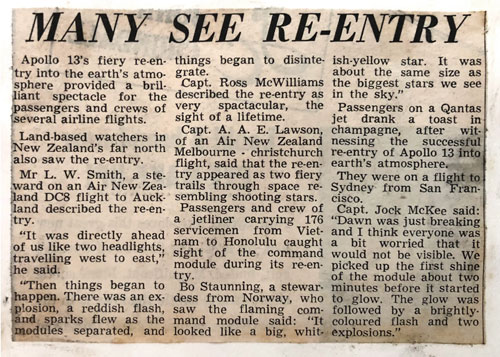

The next morning the Auckland Star carried a photograph of the re-entry proclaiming that the passengers on our flight had been the sole witnesses to ‘The Sight of a Lifetime’. It seemed that their photographer was lucky enough to get it right too! Perchance he used the settings I gave him?”