Epilogue

by Hamish Lindsay

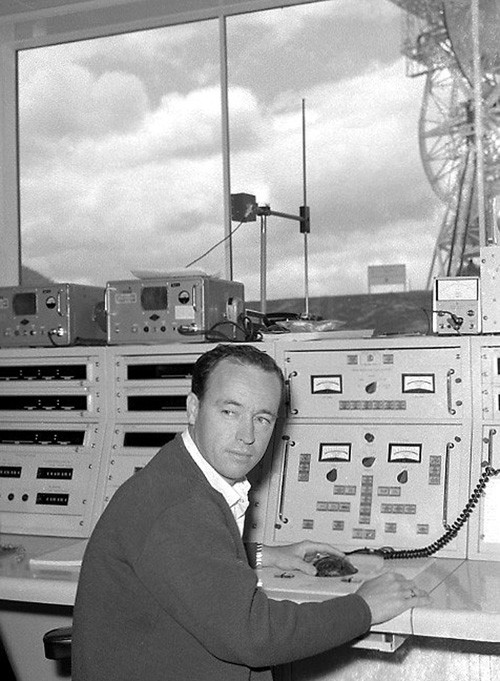

Member of the Technical Staff at Honeysuckle Creek

1966 – 1981.

|

Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station, built specially for the Apollo Moon landings,

closed its doors for the last time in December 1981 – and simply faded

away.

There were no farewells, no speeches, no parties, no wakes. All the equipment was removed, we pulled the last of the cables out, stacked the boxes, and walked out the door. During its short but glorious life, Honeysuckle Creek distinguished itself as a top station around the world in two completely different spheres – as a Manned Space Flight Station attached to the Mission Control Center in Houston, Texas, and then as a Deep Space Station attached to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

I visited the building a few years after it had been closed. It had been attacked by vandals – smashed panels, broken bricks, and litter lay around the floors. I walked down the main corridor, and remembered the many times I had walked down it carrying a Styrofoam cup of coffee to the sound of voices on the Moon’s surface, or running down to the canteen for a quick meal.

I stood there for a while – looking at the slight glow of

daylight from the one window looking out on the old antenna pad, throwing just

enough sombre, grey light over the floor, walls and ceiling to make out the

rooms.

|

|

Looking towards the deserted

USB area. From a 1989 television report. |

The middle rooms, including the Telemetry and Computer areas, were empty black

cells.

To anybody else it would have been the silence of a graveyard

– the thick windowless walls of the equipment areas blocked out all sounds

of wind and rustling leaves and the world outside. But.... to me, the silence

was alive with sounds. From the recesses of my mind came the larger than life

characters and amazing events of the Honeysuckle era. Every corner, every spot,

even above the ceiling and under-floor plinth area had its memories of people

and events.

In the very beginning, in the winter of 1966, before the sealed access road

was built, it was a cold, wild trip up to the station, sometimes taking many

hours to get to work. One day I left home at 0700 and didn’t begin work

until 1000.

My first day at Honeysuckle Creek was Wednesday July 13 1966, exactly three years before Apollo 11. We would drive in Ford Falcon sedans to the bottom of the mountains, and transfer into four-wheel drive vehicles for a rough trip up a rutted track to the empty buildings. Some tried to get their cars up by letting the tyres down and filling the trunk with rocks, or putting snow chains on. Many slithered off the track, sometimes side-swiping other cars already stranded, and had to be manhandled back, and some were gunned over the bad parts, sliding all over the place before sump-scraping to a halt on the deep frozen ruts to wait for the four-wheel drive to pull them out.

I left the Gemini Tracking Station at Carnarvon and had just arrived from a three month course at Collins Radio in Dallas, Texas, to join the other members of the station staff recruited from all over the world, from all walks of life. We began to find out about ourselves, aware we would soon have to be working as a team on this great adventure, but really had no idea of what was in store for us. At the time Apollo missions were only ideas on paper.

At first we worked on discarded packing-case work benches and furniture, while Betty and Horrie Clissold in the canteen tried to make the bare building a home for us. The antenna itself was built, but couldn’t move as there was no equipment on the station to control it. The first loads of equipment arrived and with it came the American contract technical staff to install it, under John Talbot, the NASA engineer assigned to Honeysuckle to supervise the installation.

The biggest team was the Collins Radio crew under their leader,

reserved Ray Cox. They installed all the USB equipment, which included antenna

control, cabling, receivers, transmitters, demodulators, timing and ranging

equipment.

When all the equipment was installed and checked out, along came the

NASA Super Constellation aircraft and the ground simulation teams led by

George Harris to teach us their unique operational procedures. We did not do

very well at first, and had to have a big staff shake-up before we began to

pull together as an efficient team. By this stage we had a pet kangaroo which

became so lazy that when the food was brought to where it was lying, it would

not get up, but merely moved its head to feed from the bowl. We were experiencing

quite the reverse, our tempo was warming up as the Apollo program began to recover

from the disastrous Apollo 1 fire, and we went into the Earth orbiting Apollo

7, our first manned mission.

Apollo 8 was only our second manned flight, and we thrilled to the excitement of supporting the first humans to leave the Earth’s environment and head for another world. This was the first time the bigger 26 metre stations’ capabilities were needed, and we joined Goldstone and Madrid as prime stations, handing Apollo 8’s signal to each other as the world turned under the Moon. We welded into a team with a single purpose, a purpose we could now readily define.

Then came Apollo 11 and our moment of glory when we passed on to a breathless world those first steps on the lunar surface by Armstrong. After the euphoria of the Apollo 11 landing, came the jubilant sounds of the astronauts hopping and driving around on the moon’s surface with their dissonant intercom voices full of the excitement of their experiences. Looking back now, I felt at the time it seemed quite normal to be walking and driving around the Moon. It was part of everyday life on Earth, and soon became just another odd news item in the media. We started to forget the mission dangers and failures, though we were aware that Moon missions were coming to an end.

Then Apollo 13 came along to remind us that life-threatening dangers were always looking over the astronauts’ shoulders, waiting for an opportunity to move in.

– I was at my mission station at the Ranging System, which

measured the speed and distance of the spacecraft, when I heard Swigert’s

call, “Hey, Houston – we’ve had a problem here.” None of

us were aware of what was to come with that call. Our signal had dropped suddenly

and the receiver operators were fighting to keep locked onto the spacecraft.

My Ranging System was dropping in and out of lock with the ratty signal, which

turned out to be coming from the small omni antenna on the spacecraft. I listened

to the rapid exchanges between Mission Control and the astronauts as they tried

to identify the problem. When the call came requesting Parkes, we knew it must

be a serious problem. We then went on to play a major part in finding a solution

to the Saturn IVB and LM signals on the same frequency, and keeping in contact

with the crippled spacecraft. We lived every minute of that perilous journey

home.

We were officially Prime station for Apollo

15, the first of the scientific J missions. This was our mission, the

first mission using a Lunar Rover vehicle. We gave a faultless performance.

I was taking an evening meal break and walked outside to get some fresh air. The mountains were dark and silent. The sun had just sunk below the horizon leaving behind a deep indigo blue sky, and the floodlit antenna was locked onto the signal from the Lunar Module Falcon sitting on the moon’s surface. Ignoring me, kangaroos were quietly cropping the grass beside me. I looked at the Moon behind the antenna, and turned to look through the window into the brightly lit USB room, and there was a television monitor showing Dave Scott, who I had met at Carnarvon, and Jim Irwin bounding around the lunar surface.

I felt very privileged to be an integral part of this great adventure

in the peace of the great Australian bush, without being caught up in the stressful

bustle of a big city. When communicating with any of the NASA colleagues in

America, I always appreciated I was in a wild and natural bush setting while

most of them were in the bowels of buildings buried among industrious, seething

American cities.

|

|

Dusk at Honeysuckle during Apollo

15. Photo: Hamish Lindsay. |

But we also had our hazards getting to work – I remember driving to work

for an afternoon shift and as we came around a corner we found a whole section

of the road had slipped down the steep mountainside into the valley. The first

shift car just before us had crossed it safely, so it was only minutes, perhaps

seconds, and our car could have dropped down into the valley with us on board.

All the vehicles above the slip were trapped on the mountain until they were

able to bulldoze an old track nearby, days later. A hired bus from Canberra

had to drive up to the wash-away to get the staff to work and back every day.

Sometimes enormous boulders, bigger than the cars, would roll down the mountainside after heavy rain, and one night at midnight we had to chop our way through a tree fallen across the road. The rain was a sheet of sparkling white streaks in the car’s headlights as we chopped and dragged trunk and branches out of the way. Another time I was driving home alone at 2 am when a kangaroo jumped out of the dark in an isolated part of the road, smashed the grill and radiator of the car, hopped off, and left me with a car with no cooling system. From the accident point, what normally took 20 minutes to get home, took six hours, trying to keep the engine cool in short runs.

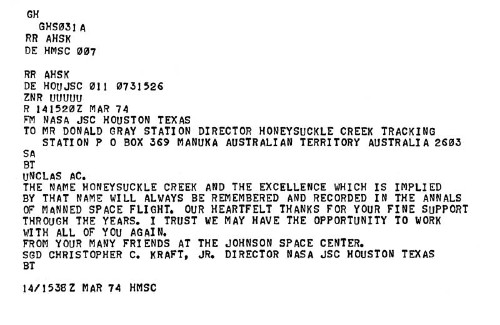

Then came the sad day in March 1974, just a month after the last manned Skylab splashdown when we said farewell to the Manned Space Flight Network, and began a new career as Deep Space Station 44, working with Deep Space Stations 42 and 43 at Tidbinbilla.

I can clearly remember the words of Chris Kraft, NASA’s first Flight Director, and later Director of the Johnson Space Center, Houston, when we met at the opening of Honeysuckle Creek in March 1967. When I asked him how he saw the future he answered, “You will be busy for many years – there will be lots of missions to the moon, simulations, stations on the moon, earth orbiting spacecraft – there will be plenty of work for you.” He was confident there was work for us stretching away into the future – I felt very happy – I had a secure and exciting job for the rest of my life.

Exactly seven years to the month he sent us his last teletype message, thanking us for our support. The job Honeysuckle Creek was designed and built for was over. There were no more Moon missions to come. We were not needed any more. We left the Manned Space Flight Network with a record of excellence as one of the best stations in the Network.

|

TWX from Chris Kraft, March 1974. |

During the Deep Space period there was the excitement of the Viking mission

to land a spacecraft on the surface of Mars where Honeysuckle Creek played an

important role. We supported missions sending probes into the atmosphere of

Venus, and the German Helios spacecraft studying the sun.

Then there were the quieter days as we sat and tracked the trailblazing space probes such as Pioneer 10 and 11, and Voyager 1 and 2 on their journeys through the solar system. Their excitement came with planetary encounters at Jupiter and Saturn. I can remember sitting at the receiver/exciter console at Honeysuckle Creek and locking onto the signal from the Voyager spacecraft at Saturn, and four hours later our receivers locking up to the signal returned to us from Voyager. I had to try and imagine the scene of our tiny spacecraft approaching this gargantuan planet with its rings. They never talked to us, these deep space probes, there were no real time pictures, not like the manned spacecraft we were used to. We never saw their pictures until they appeared days later in the media. The pictures they sent back were awesome though.

These four spacecraft are now pushing their way out into our Milky Way Galaxy, beyond the orbit of the planet Pluto, and at the turn of the century Voyager 1 was the farthest from Earth. Travelling at a speed of 62,700 kilometres per hour relative to the Sun, it was over 10.9 billion kilometres from the Earth, and the signals from the Earth-based tracking stations took over 20 hours to get to the spacecraft and back at the speed of light. Sometime in the first few years of the 21st Century the Voyagers are expected to cross the heliopause, the outermost edge of the sun’s solar wind. Then they will be free of the Sun’s influence and enter interstellar space to be tracked into the galactic void until either the fuel or electric power runs out, or their sensors lose the Sun and the signals from Earth. After we lose their signals, the Pioneer and Voyager journeys will then go on forever, possibly still travelling somewhere in the galaxy when our sun has long burned itself out, and the human race has either moved elsewhere, or become extinct. Honeysuckle Creek supported these trailblazers at the beginning of their odysseys – odysseys with no end.

Back on Earth, time ran out for Honeysuckle Creek in 1981.

The Deep Space Network had to respond to budget restrictions – this time there were no other networks to help out. I had the privilege of being a member of the team that conducted the last track, on 23 November 1981. The doors closed, the buildings fell silent. The antenna servos no longer whined into the night. Val Jefferies no longer delivered fuel to the bunkers and the Caterpillar diesels no longer throbbed away in the power house – all the lights went out. The clients of the best restaurant for kangaroos in the district were left to dine on the grass in peace.

At the end, as we sat in the operations room tracking the spacecraft, we planned golf courses, holiday centres, film studios – surely there was some use for the solid buildings? But nobody could find any use for them. Nobody wanted them. Too far away in the bush, but the antenna was still useful, and was moved to nearby Tidbinbilla, but the buildings were left to decay.

The next time Honeysuckle Creek made the newspapers, only the local ones now, they showed pictures and descriptions of the results of vandal attacks.

Then came the day I took some friends to show them Honeysuckle Creek.

The buildings were gone.

They were completely demolished in June 1992 when no use could be found for them, and were regarded as a hazard to visitors.

I also realised that gone were all the excited voices radiating to us from above the atmosphere, telling us about the unknown; the new experience of living in weightless space; the stupendous views of Earth from great distances away, just a blue ball suspended in the void; descriptions of another world, the wondrous though alien world of the Moon. Those who follow already know what to expect. An exciting, never-to-be-repeated era had passed into history.

The stations and those glorious early days of the human race’s greatest adventure now only exist in the minds of the people who were there, now scattered around the world. One by one those memories are being lost as the people pass on.

The Australian tracking stations at Island Lagoon, Muchea, Red Lake, Orroral Valley, Carnarvon, Cooby Creek and Honeysuckle Creek have all gone, now just patches of ground with special memories. A few photographs and some official documentation are all that remains.

Thanks to the foresight of members of the local government, the Honeysuckle Creek site has been preserved, with steel panels displaying some of the station’s activities and achievements. There is a picnic area to encourage people to spend some time to enjoy the bush setting, and contemplate the part played by Honeysuckle Creek in the early days of space exploration.

I have written the book Tracking Apollo to the Moon, published by Springer Verlag in London, in the hope this book will keep alive for future generations the stories of the people and the tracking stations who helped support the American Moon Landing program and its quest for knowledge about our home planet, and our part in the human race’s first steps into the alien environment of our solar system, and beyond to the Milky Way Galaxy.

– Hamish Lindsay